I’ve been a horse vet for almost 30 years. I’ve bred the mares and watched their foals come into the world. I’ve vaccinated those foals, been their dentist, rushed out to suture their wounds, and helped load them in the trailer on the way to the surgical center for a midnight colic. I’ve celebrated with their owners over their big wins and successes, and cried alongside them when chronic lameness ended their careers. When the time came, I’ve even helped these horses find restful peace.

As veterinary practices grow and demands increase, you might find that your relationship with your veterinarian has evolved to be more like the one you share with a physician. Maybe your appointments seem shorter and less personal, possibly with a vet who’s new to the practice or a resident rather than your usual veterinarian. The practice of medicine—both veterinary and human—is on the fast track. The specialized skills and technology available to “fix what’s wrong” is nothing short of amazing. Sadly though, while medicine speeds forward, something has been lost. The personal connection that’s essential to provide the most well-rounded care for each patient.

Can that something be found? Proponents of the “slow medicine” movement say it can.

What Is Slow Medicine?

Western medicine is described as having a “mechanistic” approach. If something’s broken, veterinarians and doctors perform diagnostic tests to find what’s wrong, then figure out how to repair the problem. Surgery or medications are our tools of choice.

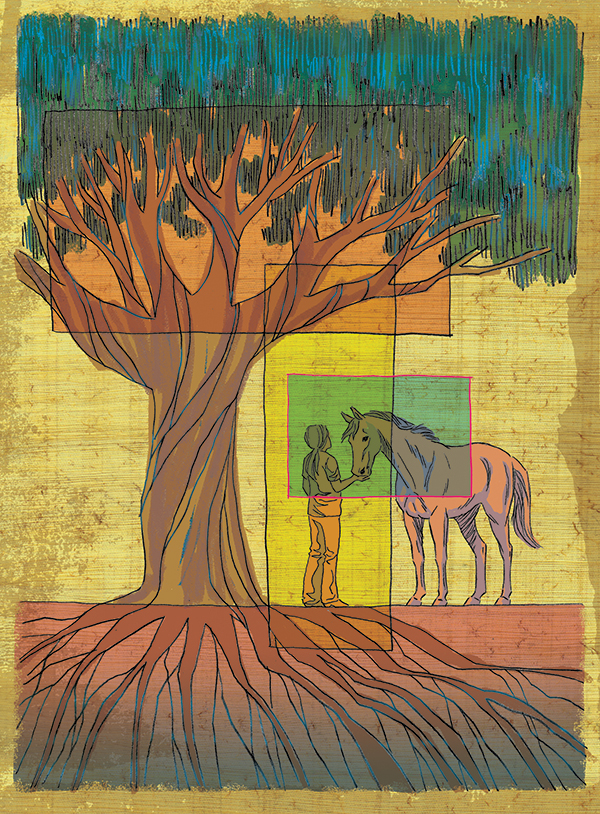

In contrast, the slow medicine approach compares the body to a plant rather than a machine. If a plant is failing, we don’t start doing things to the plant. Instead, we explore what it needs. More sun? More water? By providing what the plant needs, we allow it to repair itself.

One of the biggest proponents of slow medicine is doctor and historian Victoria Sweet. She spent 20 years of her career as an attending physician at Laguna Honda Hospital in San Francisco. In her book God’s Hotel: A Doctor, a Hospital, and a Pilgrimage to the Heart of Medicine, she describes how this old, underfunded, and largely ignored facility was a clearinghouse for the chronically ill, poor population. Homeless people or those with no ability to care for themselves lived out their lives at Laguna Honda, and the doctors and nurses cared for them to the best of their abilities. During this time, Sweet began to study the teachings of a Benedictine abbess named Hildegard von Bingen. Born in 1078, Von Bingen practiced medicine in pre-modern times. Through Von Bingen’s methods, Sweet began to appreciate the value of taking time, paying attention to the details about her patients’ lives, and treating the practice of medicine more like the work of a gardener than a mechanic.

Although advances in veterinary medicine often parallel the human medical world, chances are your equine veterinarian still practices with much more of a slow-medicine approach than your personal doctor. Your vet takes the time to get to know you and your horse, and the interactions you have are personal and face to face. Now it seems that hanging on to those slower and perhaps more thoughtful ways might benefit your horse more than we realize.

Caring for the Old

Slow medicine seems especially relevant when it comes to geriatric care. In fact, Dr. Dennis McCullough, a geriatrician from the Dartmouth Medical School, was one of the first to introduce the concept in his book My Mother, Your Mother: Embracing Slow Medicine, the Compassionate Approach to Caring for Your Aging Loved Ones. He describes slow medicine in geriatrics as “not a plan for getting ready to die, but a plan for caring and for living well in the time that an elder has left.” That might mean turning away from painful procedures or toxic medications that might prolong life, but also increase suffering—something we truly understand in veterinary medicine.

We have a geriatric patient living at our practice facility that illustrates this well. Odessa is 23 years old. She foundered several years ago, and has a chronic nasal discharge due to a large cyst that’s formed in one of her sinuses. She’s also collapsed in her stall several times in the past three years. Her owner investigated the possibility of surgery to remove the sinus cyst. At 23, Odessa isn’t considered that old, and surgery would solve the problem. Of course, the risk of complications is high—especially with Odessa’s history of laminitis and seizure-like episodes.

Enter slow medicine. Instead of pursuing surgery, her dedicated owner decided to focus her attention on providing whatever Odessa needs to maintain a good quality of life. She feeds Odessa very carefully, and makes sure she has regular farrier care to avoid bouts of laminitis. She keeps the nasal discharge at bay with Chinese herbs and the occasional course of antibiotics. Odessa is groomed daily, spends hours turned out in a pasture, and has regular acupuncture treatments. Without pursuing surgery, it’s possible her sinus cyst will progress, making her problems worse. It’s also possible her life will be cut short. But for the time she has, Odessa is a pretty happy horse.

While some might feel that no possible treatment should be left untried, others believe that modern medicine can often inhumanely complicate the act of dying by prolonging life and enabling suffering. Once again, as veterinarians, we’re lucky. Unlike our human counterparts, we have the ability to help our patients die, through humane euthanasia that eliminates pain and suffering.

One Step Further

Geriatric care isn’t the only area where slow medicine might apply, it’s just the most obvious and easy to understand. What about your performance horse? Gastric ulcers, inflammatory airway disease, and unsoundness are all common health problems than can plague a hard-working horse where a slow medicine approach is likely to be beneficial.

Consider a horse with gastric ulcers. Your veterinarian is likely to suggest gastroscopy to confirm a diagnosis, followed by treatment with oral omeprazole paste to solve the problem. This is an appropriate, effective Western-medicine approach for your horse’s disease. Chances are your veterinarian will also counsel you about feeding schedules, turn-out time, dietary changes, and other elements of your horse’s lifestyle that’ll help prevent the ulcers from returning and keep your horse healthy for the long haul. This is the slow medicine component of his care.

The same holds true for respiratory problems, such as equine asthma, especially common in show horses that spend many hours on the road. If your horse has a chronic cough, your veterinarian might recommend sampling material from his lungs or airways to rule out a viral or bacterial infection and make an accurate diagnosis about the type of inflammation present. Based on these tests, your horse’s treatment is most likely to involve bronchodilators to help open airways and corticosteroids to help reduce inflammation. That’s an example of thorough Western medicine. Your vet will also spend time helping you understand how to improve your horse’s environment to minimize his exposure to whatever might be irritating his respiratory tract. Watering his hay, providing plenty of turn-out time, and changing his schedule to make sure he’s not in the barn during cleaning time will all be recommended. The medications might work for the short term, but these slow medicine-style recommendations are all absolutely essential for his long-term health. In fact, without paying attention to your horse’s environment, his respiratory problems will surely progress over time.

Finally, what about the soundness issues that are so common in hard-working performance horses? When your horse is injured, nerve blocks, radiographs, ultrasound, and MRI can all help you discover what’s wrong, and joint injections might get you back to the show ring quickly. Until the next time. Management steps like conditioning programs, careful farriery, attention to footing, and periods of rest might prevent those injuries or at least improve the chances your horse will recover fully when he does get hurt.

When your vet comes to your farm, learns about your horse’s training and competition schedule, talks to your farrier, and advises you about the footing in your arena, she’s practicing slow medicine. When she watches you ride or calls to find out how your weekend horse show went, she’s practicing slow medicine. And when she helps you make tough decisions like whether to retire your horse from competition or even end his life, she’s practicing slow medicine.

Best of Both Worlds

In my early years as a horse vet, I sometimes felt frustrated by the limited availability of fancy machines to make a diagnosis, or by the small number of approved medications on the market that could be used for treatment. I even lamented my own shortcomings when complicated or specialized skills might have helped to “fix” a horse. Specialists were few and far between, so instead of fixing, I sometimes had to rely on providing what the horse needed to fix himself. Rest, improved stabling conditions, and better hay were often important parts of the equation. And the relationship between me, the horse, and the horse’s owner was especially critical.

Clearly, modern medicine has made things better. Colic surgery is common, and has saved many lives. Broken bones can be repaired with plates. And if a horse needs an MRI to diagnose a lameness, the technology is readily available just around the corner. I have specialists available to help with almost any complicated case, and rarely feel frustrated by a lack of available technology or effective medications. That said, we should feel lucky that equine veterinary medicine has yet to advance to the point where your vet is no longer an integral part of your horse life. I still pull the blood, read the radiographs, and call you myself with the results. As veterinarians, we understand slow medicine. And as medicine continues to move faster and faster, we should never forget how valuable that understanding is when it comes time to care for your horse.