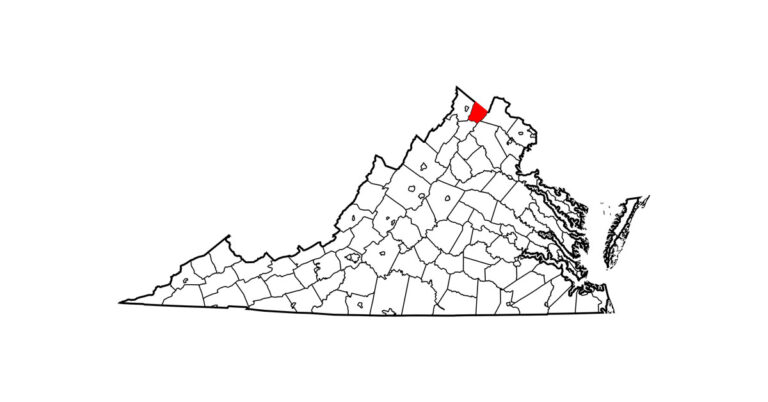

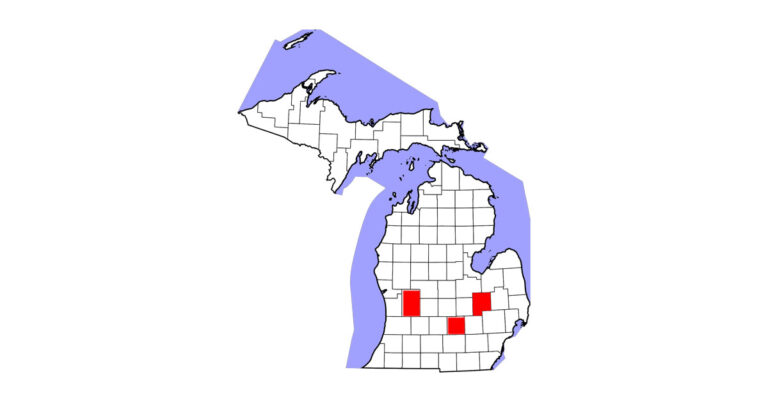

On Aug. 1, the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD) confirmed a 16-year-old Quarter Horse mare in Lapeer County positive for strangles. She presented with fever, nasal discharge, and swelling under her jaw beginning on July 12. The unvaccinated mare is reported to be recovering, and the facility where she resides is under voluntary quarantine.

The MDARD also reported a 6-year-old Miniature Horse mare in Monroe County positive for strangles. She presented with fever and multiple abscesses. Two horses were exposed, and the facility where they reside is under voluntary quarantine. The mare first became ill in May 2022 and is recovering.

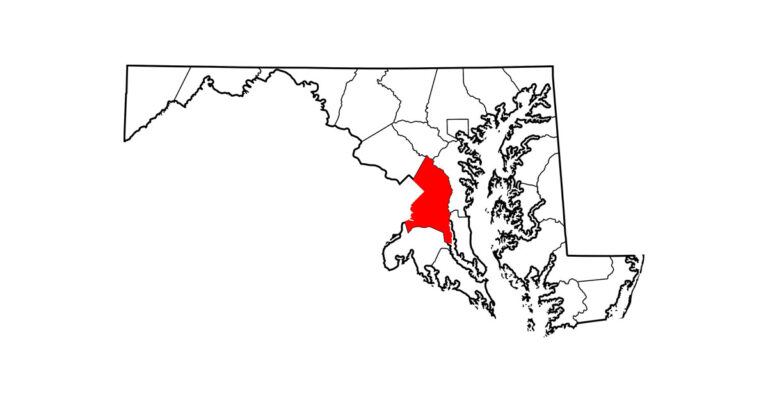

The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection reported a suspected strangles case in Marathon County. A Standardbred colt began presenting with fever, abscessed lymph nodes, and swelling under his jaw on Aug. 5 and was seen by a veterinarian on Aug. 19. The private facility is under voluntary quarantine, and no other horses were reported to be exposed.

Read More: Protect Your Horse From Strangles

EDCC Health Watch is an Equine Network marketing program that utilizes information from the Equine Disease Communication Center (EDCC) to create and disseminate verified equine disease reports. The EDCC is an independent nonprofit organization that is supported by industry donations in order to provide open access to infectious disease information.

About Strangles

Strangles in horses is an infection caused by Streptococcus equi subspecies equi and spread through direct contact with other equids or contaminated surfaces. Horses that aren’t showing clinical signs can harbor and spread the bacteria, and recovered horses remain contagious for at least six weeks, with the potential to cause outbreaks long-term.

Infected horses can exhibit a variety of clinical signs:

- Fever

- Swollen and/or abscessed lymph nodes

- Nasal discharge

- Coughing or wheezing

- Muscle swelling

- Difficulty swallowing

Veterinarians diagnose horses using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing with either a nasal swab, wash, or an abscess sample, and they treat most cases based on clinical signs, implementing antibiotics for severe cases. Overuse of antibiotics can prevent an infected horse from developing immunity. Most horses make a full recovery in three to four weeks.

A vaccine is available but not always effective. Biosecurity measures of quarantining new horses at a facility and maintaining high standards of hygiene and disinfecting surfaces can help lower the risk of outbreak or contain one when it occurs.