From the Internet…

“My 4-year-old Thoroughbred gelding started mysteriously falling to his knees. He was diagnosed with severe lower-neck arthritis.”

“I found my 6-year-old gelding in his paddock, walking anxiously around with his nose dragging on the ground. He couldn’t lift his head above his knees. Then the next day he seemed completely normal. He had enlarged facet joints between his vertebrae.”

“My mare had to be put down when she was just 11 years old because of severe arthritis in her neck.”

Have you ever had a horse that just didn’t seem quite right? Perhaps he tripped and fell, refused to move forward, or even showed vague intermittent lameness that could never be diagnosed?

[READ: Troubleshoot Lameness]

If so, it may be that he had a problem in his neck. Difficult to diagnose and challenging to treat, neck problems are confusing and often devastating. Plus they’re not as rare as we’d like to think.

I’m going to give you an overview of the structure and function of your horse’s neck so you can better understand the variety of symptoms that can point to a problem in this area. Then I’ll explain the diagnosis process and treatment options, plus discuss chances for recovery should your horse ever experience a “pain in the neck.”

Neck Structure

Seven cervical vertebrae make up your horse’s neck, extending from his poll to his chest. They attach to one another at two locations, one between the actual body of the vertebrae, cushioned by the intervertebral disks, and another between bony processes that extend along the vertebral top and sides (the articular facets).

The all-important spinal cord is protected as it runs through a canal within the middle of these vertebrae, and functions to relay messages from the brain to the peripheral nerves that supply the rest of the body. Eight cervical nerves extend from the spinal cord, through foramen or openings at the side of each vertebral junction. The sixth, seventh, and eighth cervical nerves contribute to the brachial plexus, an intersection of all of the nerves that supply the forelimbs.

When Things Go Wrong

Neck problems are typically either congenital (present at birth) or due to some kind of trauma—a fall, pulling back when tied, colliding with another horse or object. For some horses, arthritis in the neck is simply the result of long-term wear and tear, and in many cases there’s no history of trauma when a horse is diagnosed.

The signs of a neck problem can vary widely, from the obvious to the obscure. Here are some of the most common symptoms that may point toward problems in the neck.

Ataxia:

This term describes a lack of coordination. An ataxic horse will stand with his legs in unusual positions (such as too far apart) or with his hindquarters shifted to one side. Some will even stand with their hindquarters leaning against a wall. When moving, an ataxic horse can lose his balance and stagger sideways, swing wide with his hind legs when he turns, or step on himself. Some will simply stumble frequently, and may even fall down. Weakness often accompanies ataxia, and a gentle tail pull to one side as he’s walking may cause the horse to lose his balance or fall sideways.

Ataxia most commonly occurs when there’s some kind of damage to the spinal cord itself—either because of narrowing of the vertebral canal, instability of the vertebrae, or pressure from bone proliferation that can develop as a result of degeneration of the joints. In some cases, infectious diseases such as equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM), West Nile virus, or equine herpes virus can damage the spinal cord, resulting in ataxia. Your vet may suggest tests to rule out these diseases before looking for actual structural problems in the neck.

Lameness:

If your horse has a forelimb lameness that just can’t be pinned down, it could be originating from his neck—possibly due to pressure on the nerves that pass through openings in the vertebrae to supply the forelimb. Pain originating from the neck can also lead to muscular discomfort, most commonly in the long brachiocephalicus muscle that runs along the lower side of the neck and acts to pull the front legs forward as your horse takes a step. If this muscle is hurting, his stride may shorten to produce lameness. Neck-related lameness can be particularly frustrating to diagnose because it will respond poorly to typical tests performed during a lameness exam, such as stress tests or diagnostic blocks.

[READ: Horse Soundness Do’s & Don’ts]

Patchy sweating:

Damage or injury to nerves can lead to abnormal patches of sweat that appear in the area supplied by those nerves. Patchy sweating itself isn’t really a problem for the horse, but it can be an indicator that a nerve problem exists.

Muscle atrophy:

Nerves supply specific muscles to enable them to work, and if these muscles lose their nerve supply, they’ll begin to shrink—a phenomenon known as denervation atrophy. If you notice areas of shrinking muscles, particularly around the base of your horse’s neck, it may be due to nerve damage where nerves pass through the openings between the vertebrae.

Poor neck mobility:

If your horse’s neck hurts, he may be reluctant to move it. You’ll likely notice a loss of suppleness or reluctance to bend during work. You can evaluate his neck mobility with carrot stretches (most horses should be able to reach around to take a carrot held up behind the withers or toward the hip, stifle, or hock on both sides, or down between the front legs). If these stretches seem particularly difficult for your horse, or if he’s much more supple to one side than the other, it’s possible his neck is painful.

Abnormal head, neck position:

Some horses with neck pain hold their head or neck in an unusual position, either when being ridden or simply when standing in the stall. There are many reports of a horse experiencing a sudden reluctance or inability to raise his head at all—only to have it completely resolve over a period as short as several hours. In such cases, it’s possible a nerve root was being pinched where it exits between the vertebrae, a problem that can reoccur if there’s an underlying neck abnormality.

Behavior problems:

Perhaps the most frustrating problem of all is the horse that suddenly starts misbehaving in his training. He may throw his head, refuse to move, or even violently object to training demands by bucking, rearing, or spinning. It can be hard to determine whether these are just training problems, or if they might be a reflection of discomfort, such as neck pain. If you have a horse that suddenly begins misbehaving and no other problem can be identified, it might be time to look at his neck.

Pinning It Down

So you suspect the neck. How can you find out what’s really wrong? The first and most important part of diagnosing a neck problem is the clinical neurological exam. It consists of several different simple tests, listed below.

Palpation and mobility:

Pain or weakness with palpation (finger pressure) and reduced range of motion of the neck are all signs of a potential problem. To test mobility, your vet will use a carrot or other treat to ask your horse to reach around, back, and down, as described earlier.

Skin sensation:

This test, known as the panniculus response, involves using a small pair of hemostats or a ballpoint pen lightly on the skin. Your horse should twitch just as he would when a fly lands on his body; if he doesn’t react, it may mean the nerves or spinal cord are damaged.

Placement tests:

Your vet will pick up your horse’s feet one at a time and put them down in an abnormal position. If your horse is normal, he’ll immediately reset his foot where it belongs (although if he’s a super-mellow guy, this test may be hard to interpret). As I mentioned earlier, some horses with spinal-cord damage will stand with their feet and legs in odd positions all on their own.

[READ: Lame Horse – Back to Basics]

Movement tests:

Your vet will observe your horse moving in tight circles, up and down hills, backing up, and freely in a round pen or paddock. A horse with a spinal-cord problem may have difficulty placing his feet when circling, swinging his outside leg wide (known as circumduction); he also may step on himself. When going uphill, he may raise his front feet abnormally (called hypermetria), walk on his toes, and swivel his hind legs to gain strength to push himself up.

Coming down, he may knuckle over with his hind feet, or even sway a little, like a drunken sailor. (All these signs during circling and hill work are likely to be more pronounced if his head is held up in an abnormal position.)

Asked to back up, he’ll resist, and when he complies, he’ll drag his toes. When moving freely, he may bunny hop with his hind legs at the canter. Or knuckle over with his hind fetlocks when he tries to stop.

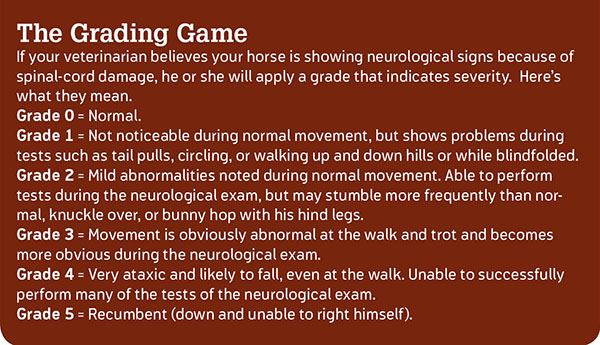

That completes the basic neurological exam. (For a summary of the grading system used to describe ataxia observed during this exam, see “The Grading Game,” above.)

Looking Deeper

If the exam does suggest a problem in the neck, it’s time to take a closer look with other diagnostic methods.

Radiographs:

Routine X-rays are typically the next step in pinpointing the underlying cause of a neck problem. Radiographs can show a wide variety of abnormalities. This includes obvious narrowing of the spinal column (which could cause pressure on the spinal cord) and bone proliferation in articular facets (which may indicate arthritis).

High-quality neck radiographs, once difficult to obtain, can now be made right at your farm with your vet’s portable digital X-ray machine. Interpreting them, however, can be another story. Although some abnormalities will be obvious, and likely to explain underlying problems, others may not be so clear.

For example, estimates say as many as 50 percent of horses have radiographic abnormalities in the articular facets at C6-C7, with no sign of troubles. In other words, your vet must interpret neck X-rays with care. Even if abnormalities are detected, further diagnostic tests might be needed to clearly identify the neck as a source of underlying problems.

Nuclear scintigraphy:

A bone scan, as it’s commonly called, can tell you whether there’s active inflammation in the bones or where ligaments attach to bone; this can be a big help in sorting out a neck problem. For this test your horse is injected with a radioactive substance that will accumulate in areas of increased blood flow. Areas of increased “uptake” of radioactivity are then detected with a special camera. Like radiographs, a bone scan of your horse’s neck must be interpreted with care.

For example, portions of the upper and lower neck will normally show increased uptake so should not be over-interpreted. However, if your vet detects a significant “hot spot” on an articular facet that also appeared abnormal on a radiograph, chances are you’ve successfully pinpointed your horse’s neck problem.

Myelogram:

If your horse is showing neurological symptoms indicating a spinal cord problem that’s more than just a “pain in the neck,” a myelogram is the gold standard for confirming a diagnosis. For this test, your horse must be put completely out under general anesthesia. A needle is placed into the spinal canal so that a contrast material (a special dye that highlights an area to be radiographed) can be injected into the fluid within the canal that bathes the spinal cord. Then a series of neck radiographs are taken with the neck in a variety of positions. On these radiographs, actual “impingement” or pressure on the spinal cord can be accurately detected. The myelogram can confirm that the spinal canal is narrowed or that instability of a vertebra is causing pressure on the cord.

Treatment

Treatment options will depend on the results of diagnostic tests—and can have variable success. If arthritis of the articular facets is identified, your vet may suggest injecting those joints with a corticosteroid to help quiet inflammation. These injections were rarely performed in years past, but are now becoming fairly routine. They’re typically performed with ultrasound guidance, and can be effective in eliminating neck-related signs for a period of time. Sadly, in many cases the signs will eventually return. This makes the long-term prognosis for a case of neck arthritis questionable at best.

If your horse is found to have malformation or instability of the cervical vertebrae as an underlying problem, more aggressive treatment might be warranted. This will help stabilize the spine and minimize damage to the underlying spinal cord. Surgical fusion of the spine with a device known as a Bagby basket can be successful at reducing symptoms. This fusion procedure stops movement of unstable vertebrae to reduce spinal-cord compression. Because of this stabilization, the articular facets will atrophy. This is because they’re no longer needed as stabilizers, and this can help the vertebral canal to enlarge.

This surgical procedure is most successful if it’s performed as soon as possible after signs are detected before the cord is permanently damaged. Experience shows that it can take up to a year for maximum improvement after surgery. And 80 percent of horses’ signs will improve by one grade, while only 50 percent will improve by two grades.

Of course, the joints of the neck are just like any other joint and may respond to common treatments targeting joint disease, such as Adequan, Legend, or oral joint supplements. Alternative therapies including acupuncture can also be beneficial for long-term management of a neck problem.

Even with better recognition of signs, improved diagnostics, and more access to treatments like cervical facet injections, neck problems remain difficult to diagnose and frustrating to treat. Only one thing is for sure: A “pain in the neck” may be a common underlying cause of a wide variety of performance problems.