I love horses. And as an equine veterinarian, one of my most common acts of kindness is to end the life of a horse suffering from the excruciating pain of severe laminitis. I’m not alone; my fellow equine veterinarians euthanize many horses each year for the same reason.

Laminitis, also known as founder, can strike any horse. Remember Secretariat? He won Thoroughbred racing’s Triple Crown in 1973, set an all-time record in each of the three races, and is considered by many to be the best racehorse that ever lived. Yet when he developed laminitis at age 19, he had to be euthanized. Then there was Barbaro. After fracturing his left hind leg in the Preakness Stakes in 2006, he became a household name. We all followed reports of the multiple surgeries and intense care he received for the following 8 months—until he foundered, and was euthanized to end his pain. Just last summer, the much-loved reining horse and popular sire Gunner, a.k.a. Colonels Smokin Gun, was euthanized because of this disease.

Why does laminitis kill? How can it be possible that even horses as valuable and well cared for as Secretariat, Barbaro, and Gunner can’t survive it?

It’s all about the pain. In this article, we’re going to take a look at how your horse’s feet function, and the physical breakdown that occurs when laminitis strikes. You’ll begin to understand why this condition hurts so much, and why it’s hard—even impossible—to break the cycle once it begins. We’ll look at the risk factors; triggers that initiate a laminitis event; and, most importantly, what steps you should take to minimize the chances that your horse ever will be a victim of this deadly disease. →

From Bad to Worse

The unique construction of your horse’s foot is nothing short of amazing. It allows a 1,000-pound animal to run, jump, and slide on the tips of his toes. Your horse is a prey animal, and this means he evolved to run fast and straight across the ground to escape from predators. Since prehistoric times, he transformed from a small, fawn-like creature with multiple toes, to the sleek, long-legged animal we know today. His legs got longer to make him faster and more efficient—and he found himself supported by only his middle toe.

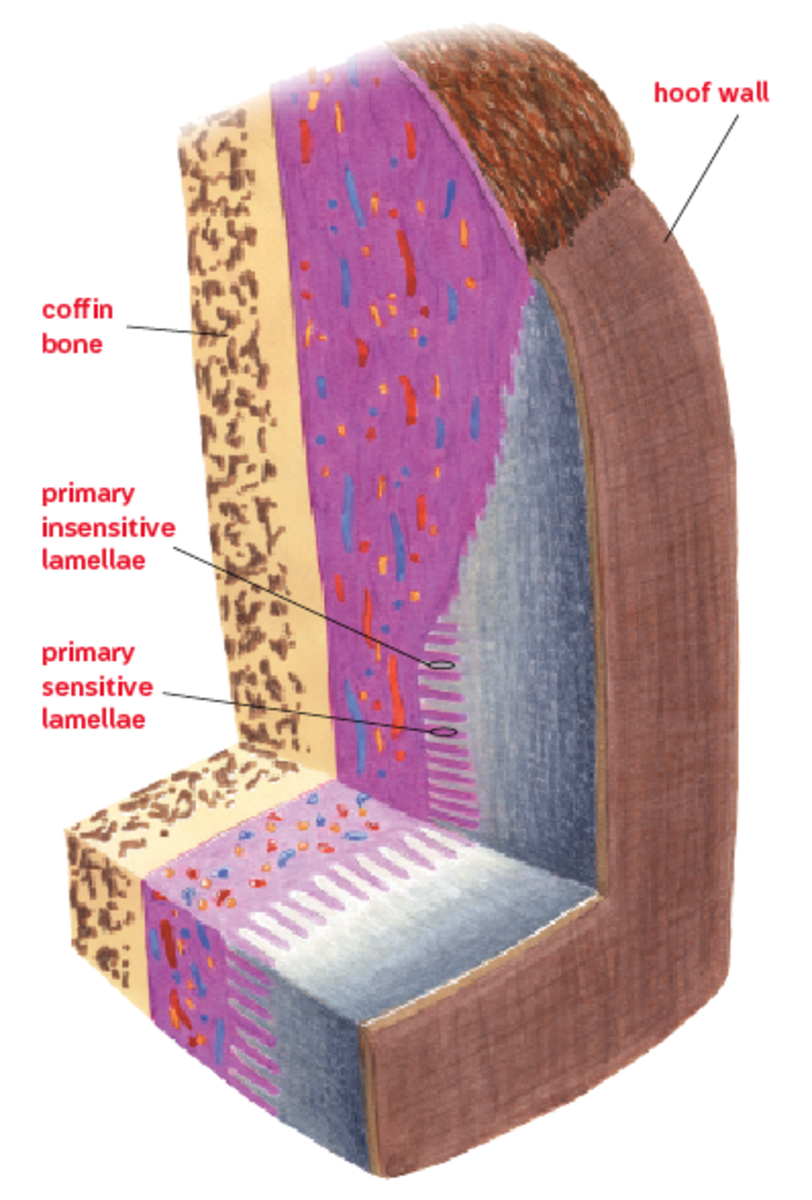

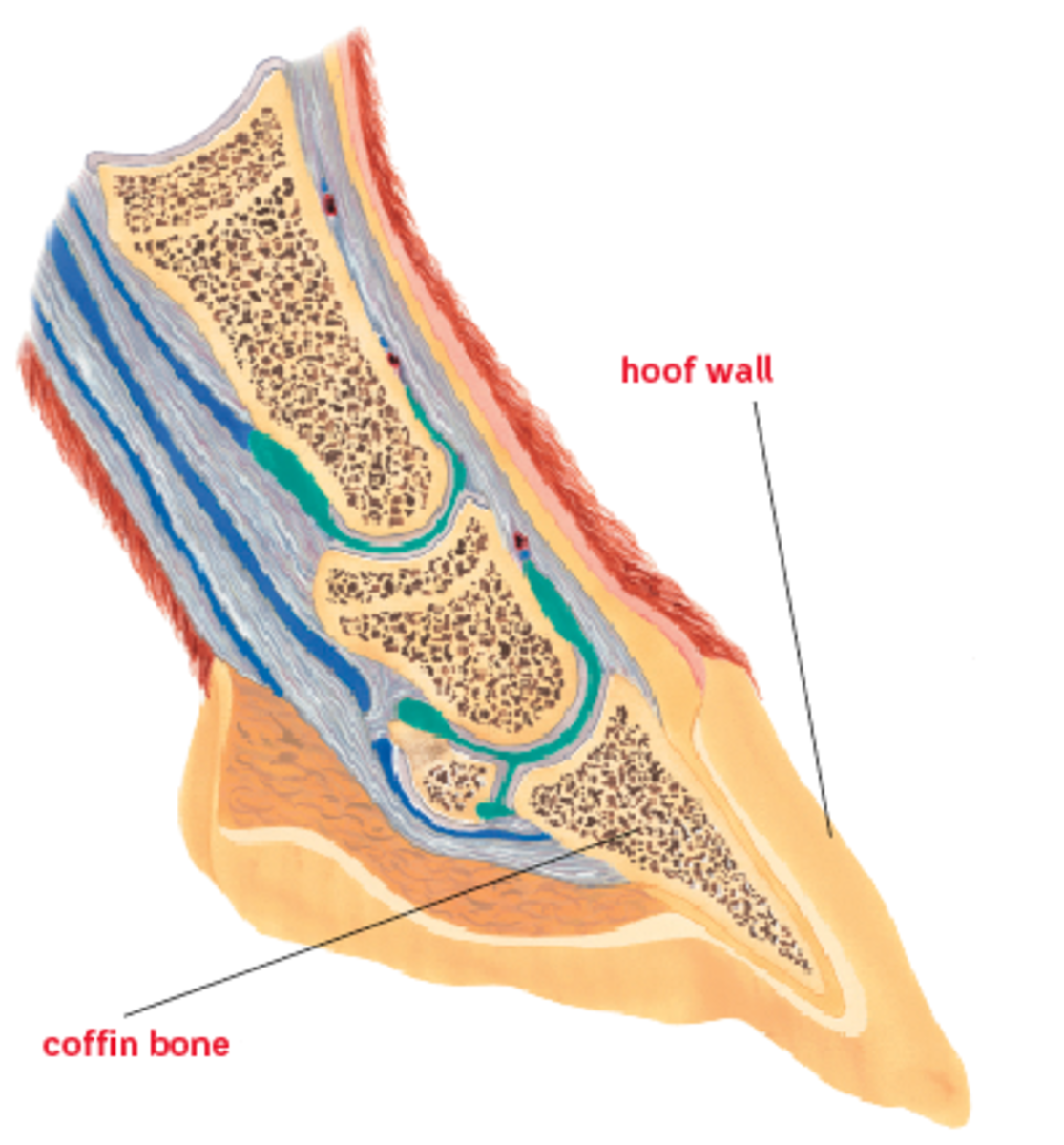

At the base of that support is his hoof, a hard, horny structure that covers and protects the bones and soft tissues of his foot. The inner surface of the hoof is made up of a series of approximately 600 serrated ridges, called the “insensitive lamellae.” Microscopically, each individual ridge looks a little like the blade of a grapefruit knife, with between 150 and 200 secondary ridges along the surface of each primary lamella.

On the opposite side, the tissue that covers the bones and soft tissues of his lower leg has approximately 600 corresponding fleshy, fingerlike projections, called the “sensitive lamellae.” Like the insensitive lamellae, each of the sensitive lamella has another 150 to 200 secondary ridges on its surface. The interlocking of these primary and secondary lamellae forms the bond that holds the hoof in place. The bond must withstand the stress of supporting your horse’s weight, even as he runs and jumps.

Each of the secondary insensitive lamellae is shaped with a rounded tip surrounded by a “basement membrane” that separates it from the adjacent sensitive lamellae. When laminitis occurs, the relationship of the cells at the tip of each lamella with the cells of the basement membrane breaks down. This breakdown can be separated into three distinct grades.

Grade 1:

Tips of the secondary insensitive lamellae become elongated, and the cells at the tip lose contact with the basement membrane. Under a microscope, small bubbles are seen at the tips where they are no longer attached. This early stage of the disease occurs before any symptoms are seen. In practical terms, this means there’s likely to be significant damage to your horse’s feet before you recognize he has a problem—perhaps the first feature contributing to the deadly nature of the disease.

Grade 2:

With each step your horse takes, the cells of the lamellae are drawn farther and farther from the basement membrane. As these layers of cells separate, connective tissue between the secondary lamellae is drawn away. The insensitive lamellae lose their “holding power” as they come in contact with one another at their base, instead of holding tight to the corresponding fleshy fingers of the sensitive lamellae. As the cells of the lamellae separate from the basement membrane, small blood vessels called capillaries are also drawn away—leading to an increased resistance to blood flow. That’s why your horse experiences a strong or “pounding” pulse in the blood vessels of his feet during early stages of laminitis—a sign that generally accompanies the onset of pain. What does this mean? By the time your horse is painful, the connection between his hooves and his feet has already suffered potentially irreversible damage.

Grade 3:

In the final stage of laminitis, there’s a complete separation of the lamellae from the basement membrane. Initially, this separation may only be seen under a microscope. When it progresses, it can be seen as a measurable separation of your horse’s bones and soft tissues from the hoof itself. The hoof-shape coffin bone rotates (the toe begins to drop) within the hoof capsule. In severe cases when all attachments are lost, it will “sink” straight down. Referred to as “fatal sinker syndrome,” this is the most terrifying of all laminitis cases: The horse is no longer attached to his hooves. Grade 3 laminitis can occur suddenly (complete separation can happen as fast as 48 hours after the process begins), or very gradually over time. In either case, the pain is constant and excruciating. Grade 3 laminitis turns deadly when euthanasia becomes the horse’s only means for relief.

Why Does Laminitis Happen?

Three primary mechanisms can initiate a laminitis episode: hormonal disorders, intestinal disturbance, and mechanical trauma. Here’s how it happens.

Hormonal disorders:

It’s all about the insulin, the hormone responsible for regulating glucose (sugar) metabolism. Insulin resistance (IR) is a common hormonal disturbance that can lead to laminitis. When glucose enters your horse’s bloodstream, insulin is released to stimulate uptake of glucose into his tissues to be processed and stored. Insulin also is involved in regulating blood flow; it stimulates dilation of blood vessels. If your horse becomes insulin resistant, it means his insulin loses its effectiveness, and the flow of blood through the vessels in his feet is compromised.

IR occurs most commonly if your horse has a condition known as Equine Metabolic Syndrome; he’s likely to be overweight, with fat deposits on his crest and tail head, and a very “easy keeper” that thrives on air. Obesity; grain overload (your horse sneaks into the feed room); and grazing on lush, green pasture grass are all major laminitis risks because they lead to increased glucose in his bloodstream, excessive insulin release, and eventual insulin resistance.

Cushing’s disease is another hormonal disease that can contribute to laminitis indirectly, primarily via its effect on insulin. If your horse has Cushing’s disease, his pituitary gland functions abnormally. The end result is an increase in the amount of cortisol (the body’s stress hormone) released into his system. Although the link between cortisol and laminitis isn’t completely clear, it’s theorized that cortisol antagonizes the effect of insulin—again compromising blood flow to your horse’s feet. Cushing’s by itself may not significantly increase your horse’s risk for laminitis. However, if your horse has Cushing’s, he’s at greater risk for developing metabolic syndrome. That’s when laminitis is most likely.

Intestinal disturbance:

If your horse has an intestinal problem such as a severe colic or diarrhea episode, the population of normal bacteria that help maintain the balance of his intestines can be disrupted. When the normal bacteria can no longer do their job, acid levels increase and his intestines become more permeable, allowing inflammatory cells and toxins to enter his blood stream. These inflammatory cells and bacterial byproducts cause blood vessels to constrict, and once again, the blood flow to his feet is compromised.

Carbohydrate overload from an overnight sneak attack on the feed room or from gorging on fresh, green pasture will cause a disruption in the intestinal imbalance, in addition to having an impact on insulin. The double-whammy effect may be a good explanation for why laminitis due to carbohydrate overload is often sudden and severe.

Mechanical:

When your horse’s feet are traumatized, his lamellae can be damaged, setting off a slow yet often irreversible laminitis episode. Barbaro’s demise was a good example of this type of laminitis. The stress from weight bearing on his “good leg” during the course of treatment for his fracture caused laminitis, literally leaving him with “no leg to stand on.” Laminitis on the opposite leg is always a huge concern with severe musculoskeletal injuries—and often marks the end of the road for these unfortunate horses.

Other causes of mechanical stress to the feet include long, hard work on very hard ground (“road founder”), or poor farrier care with chronic foot imbalance. In particular, if your horse has a tendency to grow very long toes with under-slung heels, those long toes put constant torque on the underlying lamellae that can lead to laminitis.

Prevent Laminitis From Taking Your Horse

Why does laminitis kill? And why is it so hard to treat? Again, it’s all about the pain—the constant, excruciating pain. Add to this the fact that irreversible damage often happens well before signs are recognized, and that multiple causes mean no single treatment is always effective. It’s easy to see why laminitis claims so many equine lives, and why prevention is the key. These are five steps you can take.

Recognize it early.

We’ve learned that the damage begins before your horse gets lame. That means it’s critical to recognize very subtle signs of laminitis early on so you can begin treatment immediately. If your horse looks even a little foot sore, with heat in his feet or a strong digital pulse, call your vet right away. Studies show that cold applied to the feet will help prevent the breakdown of the basement membrane that occurs before the lamellae lose their grip. Because of this, icing is very effective for minimizing progression of the disease in its early stages. Stand your horse in buckets of ice water, and follow your vet’s advice about administering anti-inflammatories such as bute or flunixin meglumine (Banamine). If you suspect laminitis, you should also avoid exercise initially. Any activity can cause additional stress to the lamellae, making matters worse. Don’t walk your horse, and don’t turn him out.

Studies show that advanced age is one of the primary risk factors for laminitis. While you can’t halt the progression of years, you should pay especially close attention to your older horse.

Monitor body weight.

Body weight is another critical risk factor for laminitis. Don’t let your horse get fat. If he’s obese, he’s more at risk for developing insulin resistance and subsequent laminitis. To make matters worse, his weight alone contributes to mechanical stress on the lamellae. To protect your horse, maintain his weight so that you can feel his ribs when you run your flat hand along his side. Adjust his rations regularly, and maintain him on an exercise program to keep him fit.

Avoid carbohydrate overload.

Even if he isn’t fat, your horse’s overnight gorge on grain, or rapid exposure to lush, green pasture could stimulate a laminitis episode. Keep locks on grain bins and close feed-room doors. If your horse does get into the grain room, call your vet immediately for advice. When it comes to pasture-grass exposure, introduce your horse to turnout gradually if he hasn’t been outside regularly. If he’s an older horse, suffers from obesity, or has been diagnosed with insulin resistance, avoid free-choice green pasture turnout altogether. A well-fitted grazing muzzle can allow him pasture time without the green-grass risk.

Diagnose and treat Cushing’s disease. If you suspect your horse could be showing signs of Cushing’s disease, such as inappropriate sweating or a long hair coat that doesn’t shed in summer months, consider testing. If Cushing’s is diagnosed, treat it. Although common tests for this disease may not identify it in its early stages, a more sensitive test (the TRH stimulation test) is now available. Ask your vet whether this test would be recommended for early identification of Cushing’s disease if your symptomatic horse tests negative initially.

Protect your horse’s feet.

Minimize mechanical trauma to his lamellae by paying close attention to his work surface, and by maintaining a regular trimming or shoeing interval. Your vet and farrier might even recommend that you have radiographs of your horse’s feet taken that show the relationship of his coffin bone to his hoof wall. Radiographs taken at regular 6- to 12-month intervals will give his hoof-care provider the best chance at keeping his feet in proper balance. Regular radiographs can be valuable for any horse, but they just might save the life of one that’s prone to laminitis.

One thing is clear:

Because of the constant, unrelenting pain it causes its victim, laminitis is a disease that’s best avoided at all cost. Once your horse falls victim to a severe laminitis episode, he may never recover. For this condition, more than any other, the best treatment is prevention