An average horse will produce as much as 50 pounds of manure a day. Fifty pounds a day adds up to nine tons a year. Now that’s a lot of poop! And every one of those piles can give you insights into your horse’s overall health status. In fact, just like heart rate and gut sounds, poop production really should be considered an important vital sign.

[READ: 7 Steps tp Easier Stall Mucking]

I’m going to teach you what’s important to know about your horse’s manure. First, we’ll take a look at normal digestion and how waste is produced. Then, we’ll consider the factors you should monitor about your horse’s manure, including the “three Cs” of color, consistency, and control. With this information in hand, you’ll learn to recognize what your horse’s poop is telling you. That manure pile may never look the same again!

Let’s shop for the items you’re missing in your barn! Amazon offers the items you need to get the scoop on poop. Add Muck Boots, pitchfork, stable fork, scoop shovel, and wheelbarrow to your cart!

Products we feature have been selected by our editorial staff. If you make a purchase using the links included, we may earn a commission. For more information click here.

Horse Poop Production 101

Digestion begins when your horse takes a bite. He produces saliva to mix with the feed he chews as he prepares to swallow. If he’s chewing hay or pasture, he’ll produce twice the amount of saliva that he will for a bite of grain or pellets. Saliva is a buffer that helps to neutralize stomach acids, and the additional saliva produced when chewing hay or pasture not only aids digestion, but is also part of the reason gastric ulcers are less of a problem for horses on high-forage diets.

After it’s swallowed, food enters the stomach, where very little digestion actually takes place. In fact, food material may spend as little as 15 minutes in the stomach before moving on. The stomach’s primary role is to help liquefy the feed to aid its passage through the small intestine, where absorption of nutrients begins.

The feed spends one to three hours in the small intestine where simple sugars, fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), fats, and protein are all digested and absorbed. Next, it moves on to the large intestine, including the blind sac called the cecum, and the loops of large colon where fermentation of fiber produces volatile fatty acids—an important source of energy for your horse. After almost all the nutrients have been extracted, the feed enters the small colon where water is absorbed and fecal balls form, ready to be passed out through the rectum. In total, it takes between 36 and 72 hours for a bite of food to be transformed into manure.

[READ: Manure Management]

Like a Diamond: The ‘Three Cs’

Just like a fine diamond, a pile of poop can be assessed according to “three Cs”—but in this case, the letters stand for color, consistency, and control. Be aware that when it comes to manure, there’s a great deal of variation between horses. And, even day-to-day changes can be normal for a specific horse. Most important, you should learn what to expect with your own horse, then pay attention when something changes. Here’s a guide to normal, along with important red flags that could alert you when something’s not quite right.

COLOR

Manure is typically a “shade of green.” You often can tell something about your horse’s diet from the color of his poop. If your horse eats alfalfa, his piles will be a more vibrant green than if he’s eating dry grass hay—and lower-quality hay often will result in a brownish tone. Other feed options can lead to normal variations in color as well. For example, beet pulp can make your horse’s manure look reddish-brown, while a diet high in oil can cause it to look gray.

Red flag: Red (bloody) manure.

Action: If you’re consistently seeing blood in your horse’s manure, call your veterinarian for advice.

Red flag:Yellowish-coated manure.

What it means: A yellow, stringy coating on your horse’s manure is most likely mucus. If you see it, chances are the manure has been delayed passing through your horse’s intestinal tract.

Action: Pay close attention. The most common reason for a slowed trip through the intestines is a feed impaction, which can lead to colic. Make sure your horse is consuming plenty of water. To boost water intake, consider soaking his hay or offering him wet beet pulp or a bran mash for a couple of days.

CONSISTENCY

A perfect pile of poop is moist, but not too wet, with formed fecal balls making up the pile. It’s perfectly normal for some horses to pass a little bit of water before and/or after they defecate. And your horse’s manure may look a little softer (more like a cowpie) after a work session, when he’s nervous, or when temperatures soar. The material within a pile of manure should be broken down, with no recognizable chunks of fiber or other feedstuffs.

Red flag: Cowpie piles in unusual conditions.

What it means: Although cowpie consistency may be normal for your horse at certain times (like after work or when he’s nervous), if it occurs at an unusual time or is especially persistent, it might mean that your horse has a gastro-intestinal (GI) upset.

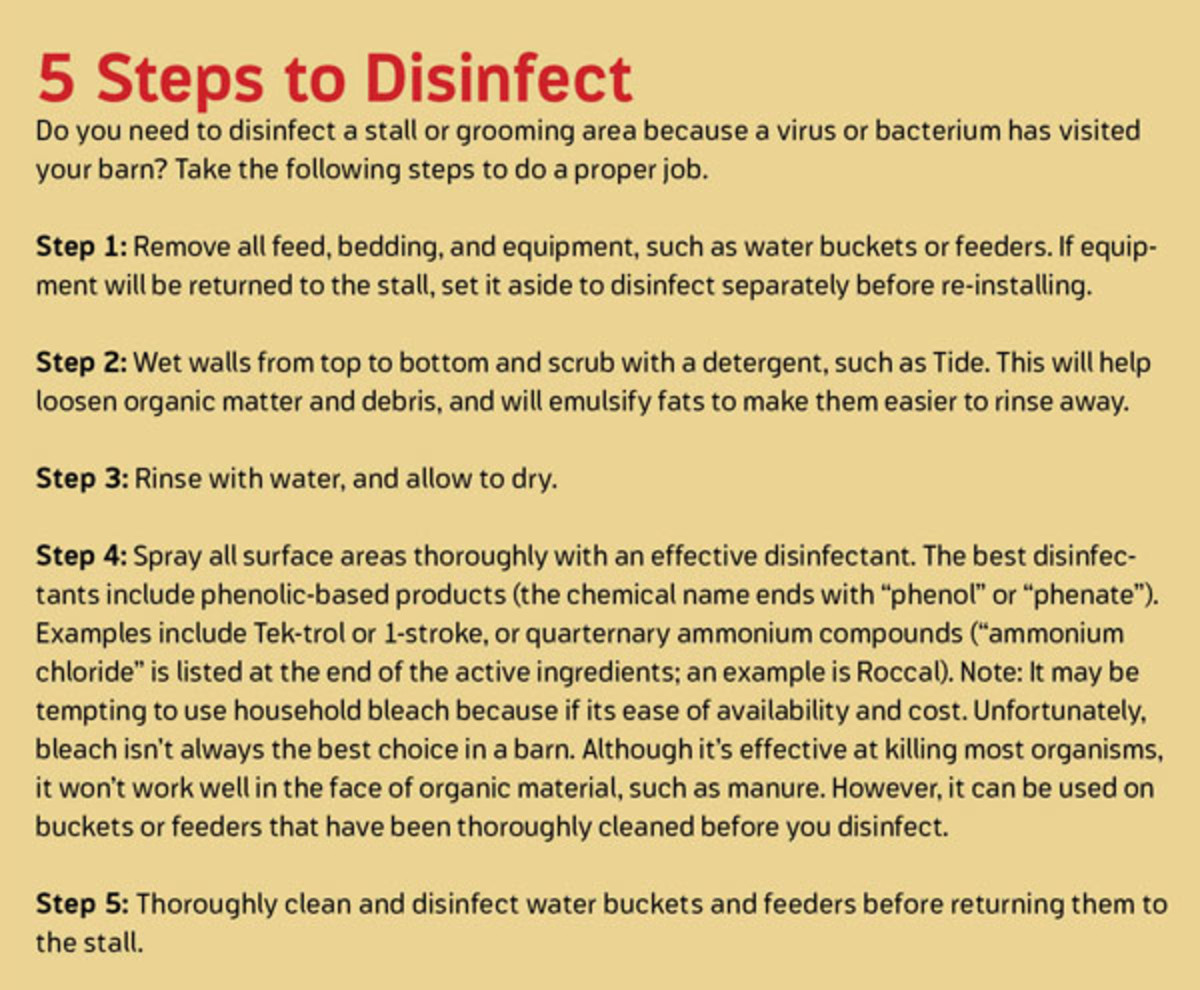

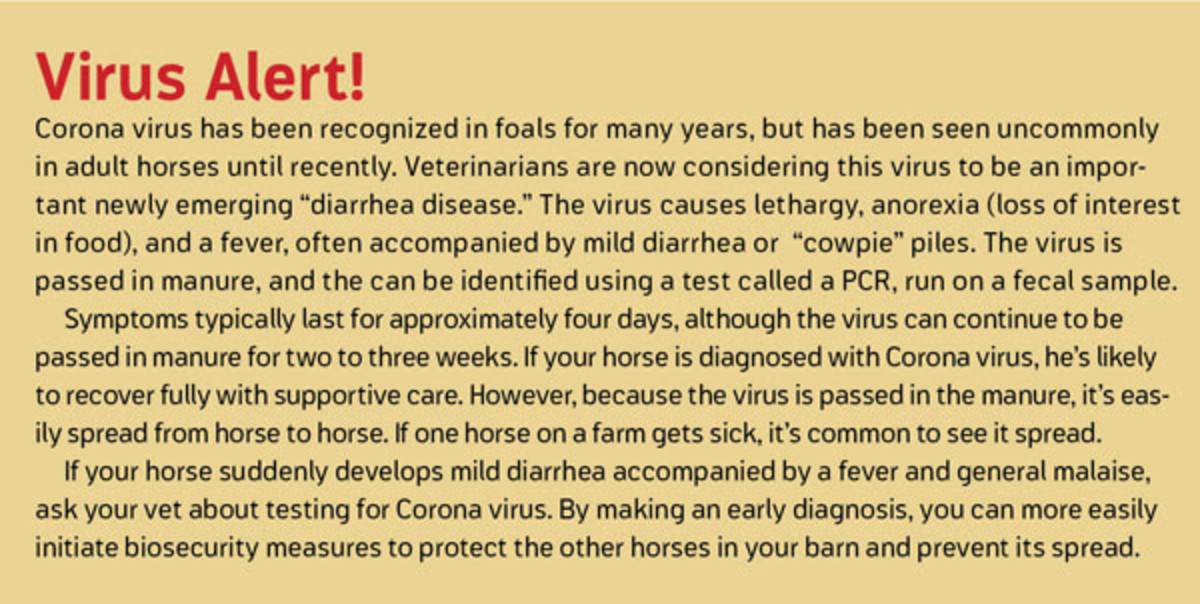

Action: Take your horse’s temperature and call your veterinarian if he has a fever or isn’t feeling well. A virus or bacterium could be the cause. (See sidebar on page 58 for information about Corona virus, cause of a newly emerging disease in horses.) A diet change can cause mild diarrhea, so if you aren’t in direct control of your horse’s feeding plan, ask whether something’s changed. Make sure your parasite-control program is up to snuff; a fecal check for parasite eggs might be advised. Consider adding a probiotic to your horse’s ration as a way to boost beneficial flora in his GI tract. If the problem persists, ask your veterinarian for further advice. Just like some people, some horses live with low-grade colitis that can result in chronic, intermittent diarrhea. Your vet may recommend a supplement or medication that will help.

Red flag: Liquid diarrhea.

What it means: If your horse is truly “squirting the walls,” he may have a serious problem. Severe diarrhea can be due to a virus, bacterial infection, or some kind of severe inflammation.

Action: Take your horse’s temperature and call your vet. If your horse is acting normal otherwise and has no fever, your vet may recommend medications to help control the diarrhea with a “wait and see” approach. If your horse has a fever, your vet probably will want to run fecal tests to check for bacteria or viruses. In either case, you should initiate biosecurity measures in your barn to minimize spread to other horses—just in case a bacterium or virus is causing your problem. (See sidebar on page 58 for information about biosecurity.)

Red flag: Hard, dry poop.

What it means:

Your horse may be dehydrated, and an impaction colic could result.

[READ: Do’s & Don’ts of Colic]

Action: Take steps to increase your horse’s water consumption, either by soaking his hay or by offering wet beet pulp or a bran mash. Monitor his behavior for signs of colic, and watch manure output closely to make sure he isn’t developing an impaction.

Red flag: Undigested oats or long hay fibers in the pile.

What it means: Although it isn’t really supported by science, the belief of many horsemen is that large particles in a horse’s manure mean he isn’t chewing well. In fact, this finding probably has more to do with the quality of the feed than your horse’s ability to chew.

Action: If your horse is normal otherwise, no action may be required. Double-check the quality of his feed, and if it’s too dry or stemmy, consider making a change. Whole oats are difficult for a horse to digest in any circumstances. Although it probably doesn’t hurt him to pass the oats undigested, they aren’t doing him a lot of good, either. Consider changing his concentrate ration to a more easily digestible option, such as a commercially formulated pellet. It never hurts to ask your vet to check your horse’s teeth, and to have him perform dental work if it’s needed.

Red flag: Worms.

What it means: If you see actual worms in your horse’s manure, he’s probably carrying a heavy parasite load. (Note: If you just dewormed him, don’t be surprised if he passes a dead worm or two. This is especially common in youngsters, or horses that aren’t on a regular deworming program.)

[READ: De-Worming Advice]

Action: Call your vet for advice. He can recommend a deworming program that will help you get control.

CONTROL

Your horse should pass manure between six and 10 times per day—more frequently if he’s a stallion or young foal. In some situations, pooping has a social function. When he’s in a herd, your horse will pass a pile to send a message to his herd mates that says, “I’m here.” In turn, his buddies may poop right back to say, “Me, too.” Stallions will pass manure to mark territory, and may even poop on top of other horses’ piles. Geldings that retain some stallion-like tendencies also may exhibit this behavior.

It should take approximately 15 seconds for your horse to pass a single pile. He’ll stop, raise his tail, adopt a wide-legged stance, and then push out the manure. When he’s through, he’ll contract his rectum several times before assuming a normal posture and walking away.

[READ: Biosecurity Measures for Horses]

Red flag: Fewer manure piles than normal in your horse’s stall or paddock.

What it means: If your horse’s manure production is down, he may be eating less than normal because he doesn’t feel well. Check to make sure he’s being fed appropriately, and that he’s cleaning up his meals. It’s also possible that something’s going on to slow movement through his GI tract, putting him at risk for an impaction colic.

Action: Take your horse’s vital signs. If he has a fever or any other sign that he’s not feeling well, call your vet. If all seems well, consider soaking his hay or offering him wet beet pulp or a bran mash to help prevent a full-blown impaction colic from occurring. Most impactions start developing days before your horse ever shows actual signs of colic.

Red flag: Your horse is taking longer than normal to pass manure, or straining to poop without producing a pile.

What it means: Your horse could be experiencing GI discomfort due to gas or an impaction. This can be an early sign of colic. He might also have a physical obstruction that’s making it difficult to pass manure, such as a mass in his rectum or a foreign body.

Action: Take your horse’s vital signs, and call your vet. Soak his hay, and offer wet beet pulp or a bran mash to help soften his manure.