It only takes one bad step. When a critical soft tissue structure is injured, your horse could be fine today, then lame for months or even years to come. In fact, a serious soft tissue injury can be even more devastating than a fracture, especially for a performance horse. Tendons and ligaments not only heal slowly, they’re also often weakened after healing—meaning they can be reinjured easily.

Because soft tissue injuries can have such serious consequences, treatments that improve healing are in high demand. But before we talk about those, we’ll first review the basics about tendon and ligament structure so you can understand how injuries happen and how they heal. Because an accurate diagnosis is so important, we’ll also explain recent advances in soft tissue diagnostics.

Finally, you’ll learn why rest and rehabilitation are such important parts of successful soft tissue treatment. You’ll be able to refer to treatment options beginning on page 65 for an overview of new technologies being used to improve healing.

[READ: Protect Soft Tissue With Standing Leg Wraps]

Key Structures

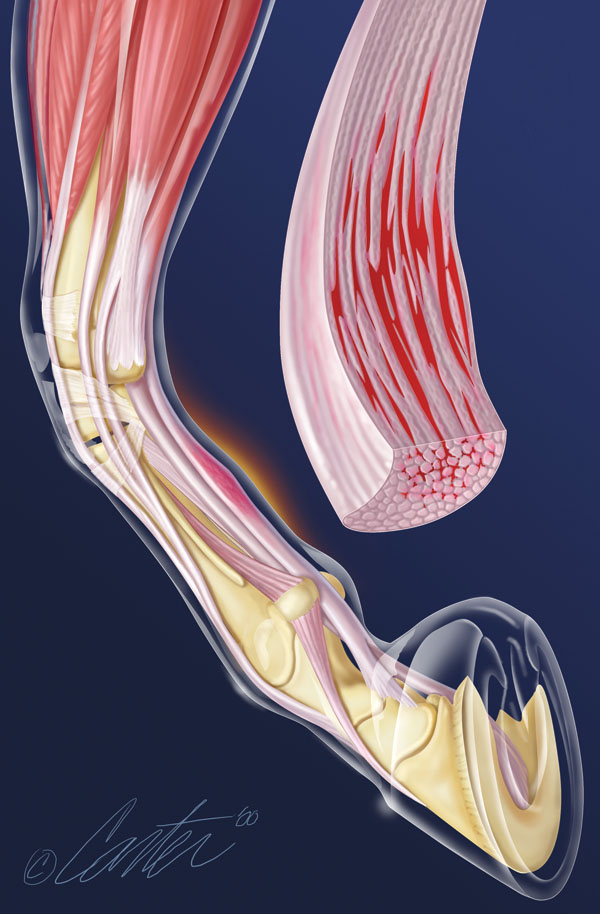

Tendons facilitate the attachment of muscle to bone, and provide the pulley through which muscles have their effect. Basic tendon structure consists of a series of parallel fibers that come together in multiple bundles, similar to the small wires within an electrical cord. The small tendon fibers within each bundle are crimped into small waves that allow them a small amount of flexibility to aid in shock absorption. Each individual tendon can be broken into three zones: the attachment at the end of the muscle, the actual body of the tendon, and the point where tendon joins with bone.

Ligaments are connective tissue structures that attach bone to bone across joints to help provide stability and control movement. They can be situated within the joint capsule (intracapsular), can attach to the joint capsule (capsular), or can be completely outside the joint capsule (extracapsular). Like tendons, ligaments consist of a series of parallel fibers that come together in a bundle. In general, they’re less elastic (stretchy) than tendons.

When Things Go Wrong

A soft tissue injury most commonly occurs when the tendon or ligament is stretched beyond its capacity, causing the fibers to tear. These injuries can be the result of a sudden trauma (like falling in a hole or twisting during a sudden move). Or, they can be due to repetitive movement that causes gradual weakening and an eventual tear. Injuries most commonly occur either within the body of the tendon or ligament or at the point where it attaches to bone. An injury at the junction of bone and soft tissue is called an enthesopathy.

Following injury, soft tissue structures go through three stages of healing, beginning with the inflammatory stage that lasts approximately seven days. During this stage, increased blood flow carries much-needed molecules to the area to help remove dead tissues and clean up debris. But it also leads to the heat and swelling you may see when an injury first happens.

This clean-up is necessary before true healing can begin, yet the inflammation that accompanies it also can cause further damage if it goes unchecked. This is the stage where treatments aimed at controlling inflammation, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, icing, and cold hosing, may be beneficial.

The second stage of healing is the period when healing cells begin to regenerate tissues. A scaffolding forms across torn fibers that then supports the collagen fibers that will be laid down to fill the injury.

Initially, these fibers are haphazardly arranged and weak. During this period, which can last for several months in a severe injury, controlled movement (usually hand walking) begins to be important to stimulate tissue regeneration. This is the stage when newer therapies aimed at stimulating tissue regeneration—such as stem-cell therapy or platelet-rich plasma—are most likely to be effective.

The final stage of healing is remodeling, when the tendon and ligament fibers begin to rearrange themselves into a normal pattern. Progressive, controlled exercise is crucial at this point to encourage fibers to heal along normal lines of stress. If proper remodeling doesn’t happen, fibers can remain randomly lined up. The structure will be weaker and possess less elasticity after healing is complete, making it more at risk for future injury.

[READ: Your Horse’s Lumps & Bumps]

Making the Diagnosis

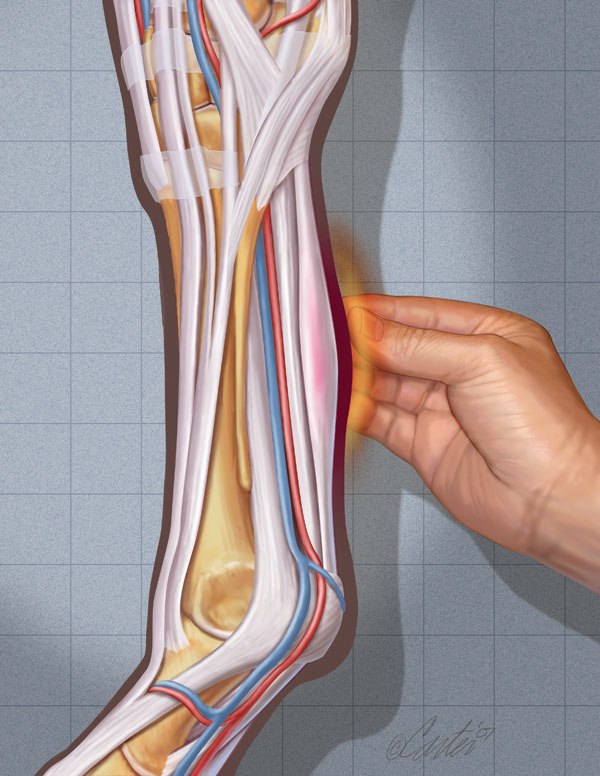

If your horse is lame and you see an obvious hot, swollen tendon, diagnosis can be simple. An ultrasound exam by your veterinarian should identify the injury and its severity.

Sadly, though, it’s not always quite that easy. Limited blood flow means many soft tissue injuries can occur with no heat or swelling at all. In fact, the suspensory ligament, which is one of the most commonly injured soft tissue structures, typically shows no sign of heat or swelling when it’s hurt.

Even more frustrating is the fact that a smoldering soft tissue injury can cause only very subtle, intermittent signs of lameness. This means many go unrecognized until they’re severely damaged. The same steps used to diagnose joint disease are used to definitively diagnose tendon and ligament injuries. An accurate diagnosis is necessary both for targeted treatment, and for monitoring healing progress.

Clinical exam. A thorough clinical examination by your veterinarian is usually the critical first step. As with any other lameness, palpation, stress tests, and diagnostic blocks can help pinpoint a structure that’s been injured.

Ultrasound. Ultrasound exam is the most common diagnostic tool used for examining soft tissues. Defects in the tendon or ligament will appear as darkened areas where fluid has accumulated, and swollen or enlarged structures can be identified with measurements. If your vet sees an obvious abnormality on the ultrasound exam, he will typically take measurements to determine how severe the injury is and use these measurements to track healing progress during rehabilitation.

Radiographs. You may not think radiographs would be useful for evaluating soft tissue injuries, but when those injuries happen at the junction between soft tissue and bone, they can be very helpful. Reaction of the underlying bone at a point of tendon/ligament attachment can help confirm a diagnosis and may help guide treatment choices. Fragments of bone can also be pulled away at the attachment site and will be seen on radiographs.

Nuclear scintigraphy. In some cases, an injury at the bone/soft tissue interface may not be seen on either radiographs or ultrasound. Here, nuclear scintigraphy or a “bone scan” can be very helpful. In fact, it’s pretty common for an injury at the point of attachment of the suspensory ligament to look normal everywhere but on a scintigraphy exam. Scintigraphy can also be helpful for injuries in structures that are difficult to see with ultrasound, such as the collateral ligaments of the coffin bone that are hidden within the hoof wall.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI produces a detailed picture of all of the structures in the area imaged, and can give the most accurate answer for a soft tissue injury. MRI exams may be performed either standing or under general anesthesia. In general, standing MRIs are best for examining structures from the fetlock down, where movement is less likely to be a problem, while general anesthesia will be necessary for structures above the fetlock.

Rest Is Best

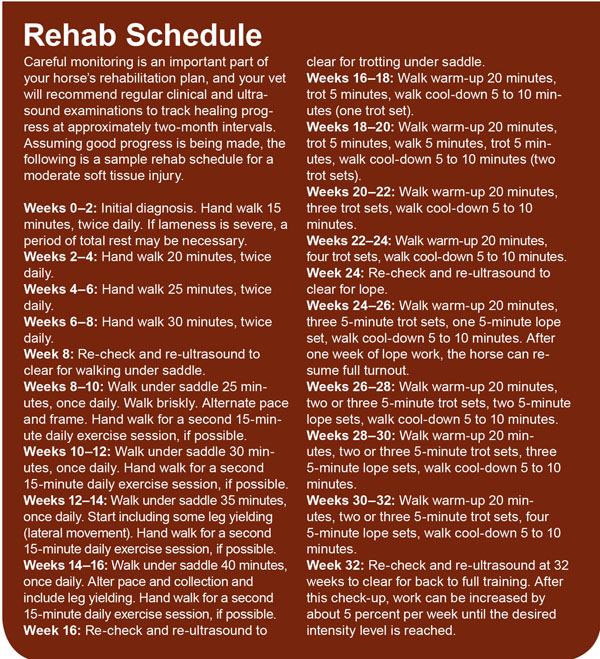

Although there are many new and exciting therapies designed to help stimulate proper healing of tendon or ligament injuries, some experts still question whether there’s any benefit beyond extended rest and careful rehabilitation from any of these treatments. One thing is clear, however. Proper rest and rehab are critical for a successful outcome, whether additional therapies are used or not.

It takes a minimum of six months for most soft tissue injuries to heal, and many take nine months or more. If exercise levels increase too quickly, the injury can become worse. If it increases too slowly, strength and athletic function can be lost. (See the sidebar on page 66 for a sample rehabilitation plan.)

It’s interesting that pain following even a severe soft tissue injury may only last for a period of three to eight weeks—ending long before healing is completed. That means that just because your horse is sound a month or two after injury doesn’t mean he should go back to work. An extended period of progressive exercise is crucial for successful healing. Although you may decide to pursue one of the new and exciting treatments outlined in Treatment Options, below, your horse’s recovery from his soft tissue injury will still require a careful rehabilitation plan.

[READ: Equine Soundness Do’s & Don’ts]

Treatment Options

In addition to rest, several medications and treatment modalities are available for healing of soft tissue injuries. Here’s a rundown of how they work, their benefits and downsides, and costs.

Stem-cell therapy. Stem cells are immature cells that transform into the cell type that’s needed at the site of injection into a soft tissue injury. They can be collected from the horse’s fat or bone marrow and processed (autologous stem cells) or obtained commercially from another horse (allogenic stem cells). This therapy may encourage faster, better healing. It can be particularly useful for an injury that isn’t healing well with conservative therapy. The therapy is expensive and can cause adverse reactions, including marked heat, swelling, and pain; this is more likely with allogenic than autologous stem cells. Some experts question efficacy and believe lesions may heal just as well with rest and rehab alone. Cost is $2,000 to $3,000 per injection.

Tildren. This medication is administered intravenously and acts to inhibit the activity of osteoclasts, which are the cells involved with cleaning up inflamed bone. Tildren can be administered daily for 10 days, or all at once slowly in a bag of fluids. It’s effective medication for controlling bone inflammation in injuries at the attachment of ligament to bone, which can be difficult to heal. It’s not as useful for soft tissue injuries that don’t involve bone. Tildren can cause transient cramping and colic-like symptoms immediately after administration. It’s expensive at $1,000 to $1,200 per treatment.

[READ: Therapeutic Equipment for Horses]