Have you ever asked yourself why you have your horse shod? Is it because you always have? Or because all your friends’, competitors’, or peers’ horses are shod? Or maybe because you believe (or somebody has told you) that your horse has bad feet and must wear shoes? Under the right circumstances, many horses can go barefoot, as long as their owners are armed with knowledge to make the right decision.

[READ ABOUT: Horse Hoof-Care Help]

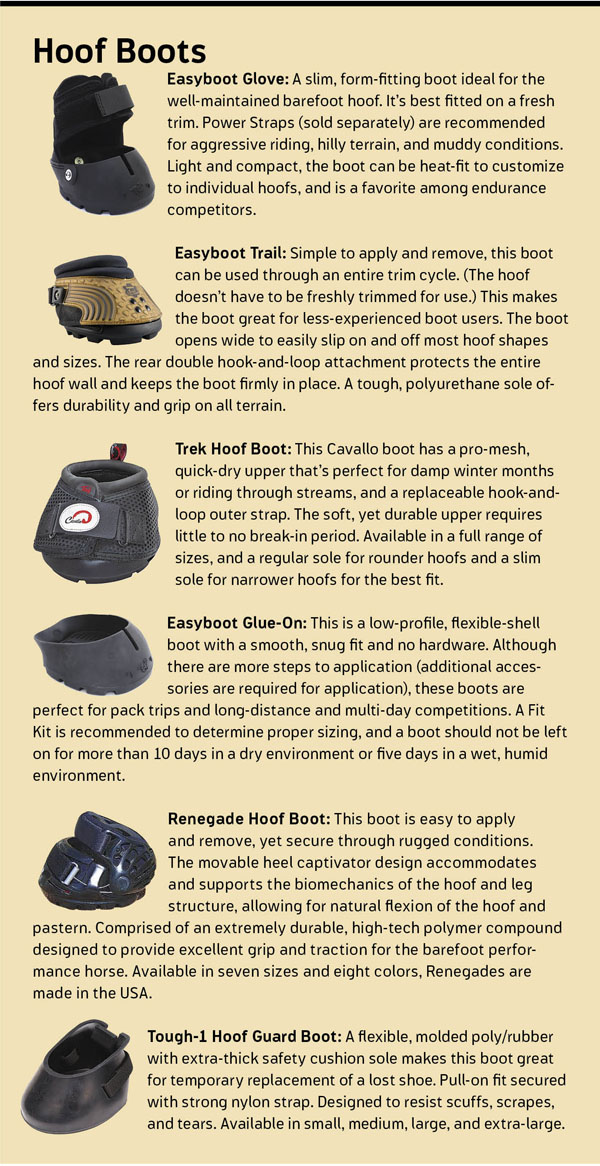

Here we’ll examine the benefits of going without metal shoes, give insight into how to transition your horse away from shoes (if it’s right for him), and review three cases of owners who transitioned to barefoot or decided to stay with shoes. We’ll also detail some hoofwear products available to protect the feet of horses without metal shoes.

Advantages of Alternatives

Pete Ramey, a farrier specializing in rehabilitation of hoof problems as well as a well-known author and clinician, sees a deeper issue than just metal shoes versus barefoot. He points out the array of options between going 100-percent with metal shoes or 100-percent barefoot. As a longtime practitioner helping horses regain healthy hoofs and soundness, he says, “I avoid the term ‘going barefoot,’ because it’s more complicated than just pulling metal shoes off and hitting the trail. If metal shoes are working for you and your horse is sound, stick with them. Metal shoes can be convenient for the owner.

However, if your horse has soundness or performance issues, you should be aware of the possible advantages of getting away from metal shoes temporarily or permanently.”

Beyond metal shoes nailed on full time, there’s a spectrum of hoof-care options, from going completely barefoot all the time to using various boots or glue-on shoes when needed for protection. Here are six of the benefits of getting away from metal shoes.

Better use of the entire foot. The hoof wall, sole, frog, and bars are all engaged in a bare foot, as opposed to the hoof wall bearing almost all of the weight with a metal shoe nailed to the perimeter of the foot. A metal shoe doesn’t ever fully release pressure to the solar corium (the layer of blood, nerves, and connective tissue that lies under the sole and surrounds the coffin bone) because it’s clamped on and limits the release of pressure. The solar corium can be easily damaged by compressive forces. With a bare foot or booted hoof, the sole is fully loaded while the hoof is on the ground, but fully unloaded when the hoof is in flight. That’s a much healthier scenario and can prevent serious soundness issues.

[READ ABOUT: Barefoot Strategies]

Better shock absorption and energy dissipation. Barefoot and booted horses’ hoofs are better able to absorb shock and dissipate energy than metal-shod horses’ hoofs, which can equate to increased performance and longevity, particularly on hard surfaces.

Vertical flexion of the hoof capsule. The back part of a horse’s hoof is designed to flex vertically, or twist, which aids the horse in negotiating uneven terrain, hitting rocks sideways, or when moving through a turn. This flexion takes a tremendous amount of torque off the horse’s joints and collateral ligaments (which help hold the joints together). A metal shoe on hard terrain can damage the hoof’s soft tissues and the hoof wall.

Versatility. A horse without metal shoes can be fitted to various boots for any given situation. Boots offer different treads and insoles for changing conditions—similar to a human being able to choose a hiking boot or running shoe. Usually, no one setup is appropriate for every condition a horse encounters.

Economics. Shoeing and trimming prices vary across the country, but stay fairly proportionate to each other, and trimming and shoeing intervals are roughly the same. If a professional charges $60 to trim and $120 to shoe with metal, clearly the trim is a savings. A pair of hoof boots can cost $150, but last much longer than a set of horseshoes, which are worn for a 5- or 6-week period. Boots can last a desert endurance racer 500 miles or more; therefore, a more casual rider could get many years from them.

Overall hoof health. Anything you can do to improve hoof quality—nutrition, exercise, etc.—will improve the health and longevity of the whole horse.

Transitioning to Barefoot

Done correctly, “going barefoot” doesn’t simply mean you stop putting shoes on your horse, according to Ramey. “There’s an entire package of changes needed to successfully go without metal shoes,” he says. “Those changes yield a healthier, happier horse, and can boost performance and provide better longevity.” Here are five considerations.

Diet. “The horse’s diet should be improved so that he can grow the best hoof his individual genetics will allow,” he continues. “This typically means feeding less sugar and starch (too much of those can compromise the attachment of the hoof wall) and following a more scientific approach with mineral supplementation.”

Everyday footing. Your horse’s turnout environment should match your riding terrain so that his hoof encounters similar terrain during everyday life that it’ll encounter during work under saddle. “Provide variable terrain in turnout—grass, pea gravel areas, hard terrain, and soft terrain,” suggests Ramey. “Drain muddy areas when possible, and keep urine and manure cleaned up. If matching turnout to riding terrain is impossible, your goal should be booted riding, not barefoot riding. Turn out a barefoot horse only if he’s moving well in his turnout environment. Otherwise, use boots or glue-on shoes (assuming that these provide comfort and correct movement). Apply the same logic and consideration for riding.”

Exercise. Increase your horse’s exercise, particularly if he spends much of his life in a stall. Hoof boots must be used if he’s not 100-percent sound during riding. Also, if not 100-percent sound during turnout, hoof boots or glue-on options should be used there, as well.

“The growth of the foot—healthy or not—is a product of how it hits the ground,” explains Ramey. “Compensative movement causes poor or pathological hoof growth. Correct movement causes correct hoof growth. For barefoot riding, the horse needs the healthiest hoof possible. If barefoot riding is your goal, riding in hoof boots is usually the quickest way to get there—the correct movement typically provided by hoof boots causes healthier hoof growth, which in turn may cause the horse to no longer need the boots. If the horse is limping or compensating for foot pain during rides, you probably will never grow a foot healthy enough to ride barefoot without pain.”

[READ ABOUT: Transitioning from Shod to Barefoot]

Sound hoof care. Find a farrier or trimmer who has experience and success with transitioning horses away from metal. This professional should know how to do a barefoot trim, which is different from a shoe-ready trim, and carry a stock of hoof boots and/or glue-on options to be able to fit the horse immediately when the shoes are pulled. Contact the American Hoof Association (AHA), Pacific Hoof Care Practitioners (PHCP), or Equine Science Academy (ESA) to see if there is a competent professional in your area. Proper fitting and selection of hoof boots is as critical as it is for metal horseshoes.

Three True Stories

Who better to ask about their experiences with barefoot horses than top-level competitors? From small, light Arabians and a tough-footed mustang to a heavily muscled Quarter Horse and a massive Warmblood, they’ll describe their varying degrees of ease and success with shoes and without.

Easy Barefoot Transition

The owner: Tennessee Lane, owner of Remuda Run in Fort Collins, Colorado; an intense and successful endurance-racing competitor with a second-place finish at last year’s Tevis Cup. She keeps more than 30 horses, including working Quarter Horses in addition to her endurance Arabians. None of her horses wear metal shoes, and she’s taken over all of their hoof care herself, trimming and booting when necessary.

The horse: Arabian mare Pixiedust, age 9, is currently in transition.

The story: Pixiedust is doing so well in her short venture to being barefoot that she was scheduled to compete in the 2015 Tevis Cup without metal shoes, less than a month and a half after Lane pulled them. “Her feet were too long and unbalanced,” Lane says. “I knew I could help her within three trimmings. After only the first trim, she’s already booted and sound for training rides on rocky terrain and comfortable barefoot in her pasture. She’ll do Tevis this year in glue-on shoes, and I have absolute faith she’ll complete that ride.”

More insight: “The average horse I come across, no matter the breed, can ultimately go without shoes,” Lane explains. “With proper trimming, nutrition, and exercise, a lot of them make the transition fairly quickly.” Another Remuda Run horse, the hard-working, ranch-bred Quarter Horse gelding Chicosa, also smoothly transitioned to shoeless and has never looked back in the 10 years since. “He’s a big, beefy horse and when I got him at age 6, his body was trying to put out a good hoof, but his shoeing job was predisposing him to long toes and underrun heels. I pulled his shoes and trimmed his feet. Just a few weeks later, he was functional and happy. By his third trim, his hoof angle matched his pastern angle; his heels supported his skeleton; and he’s been fit, healthy, and rock-solid ever since.”

Time and Effort Required

The owner: Shannon Peters, San Diego, California; U.S. Dressage Federation bronze, silver, and gold medalist and three-time national championship competitor.

The horse: Flor De Selva, aka “Squishy,” a 15-year-old Westfalen gelding.

The story: Not every horse who ends up comfortably shoeless has an easy time getting there. But Squishy, a massive horse at 17.2 hands and 1,400 pounds with a considerable history of hoof problems, has a success story, albeit with time and effort.

In 2010, Grand Prix dressage horse Squishy was the first horse Peters tried barefoot. “He’d had soundness issues in multiple types of shoes,” she explains. “He’d be fine for one or two shoeing cycles, and then we’d have to make a change. I ended up taking him barefoot for a while just to give his feet a break, and he was more sound without shoes than with them.

“Squishy never had great feet,” she relates. “He had thin, weak soles, with little concavity, and weak walls. On top of that, he contracted Lyme disease, and over the next four years, he had laminitis four times. Each time, we had to work on building a new, stronger foot again.”

Peters says conscientious trimming has been the first line of defense with Squishy. “Between great trimming and booting, we were able to get him through those tough times. We’ve also experimented with the new Easy Shoe to help him be comfortable. He’s been healthy now for more than a year, and his feet finally have hit their stride. It’s taken five years, but he’s beaten the odds to come back and be sound barefoot, and he just competed at Grand Prix level without shoes in April.”

More insight: “Squishy’s situation started my barefoot education,” she continues. “Now I take every horse barefoot. Some go directly out of shoes with no problem, and others have foot pathology that takes more time.”

Not in the Cards

The owner: Sue Summers, Rice, Washington; endurance competitor who’s raced at the FEI level for 15 years, and tries to go barefoot with her horses when possible. Summers shoes her own horses (she attended a farrier school) and admits that with as many horses as she keeps, it’s more convenient to shoe with traditional metal shoes.

The horse: Mags Motivator, aka M&M, a 20-year-old race-bred Arabian gelding.

The story: M&M is a horse Summers feels wasn’t a good candidate to go barefoot, even with boots. “He has a tendency toward thin soles, low heels, and long toes,” she explains. “I wedge-padded him and frog-supported him his whole 11-year career in which he competed heavily and even won several FEI-level competitions. He really needed the frog support, which increased stimulation and blood flow, and wedges to get his heel up, which would have been hard to do without metal shoes. He’d have bruised too easily, and I would have been afraid for his tendons without boosting his heels, though with today’s boots, that can be done, too. He stayed sound for me, and is now retired from endurance at age 20.”

More insight: “It’s time-consuming to boot, figure fit for each horse, and keep the boots organized,” Summers says. “If I had only one or two horses, I’d be more inclined to have them go barefoot.

“Whether I shoe with metal shoes also depends on the horse’s job,” she continues. “Since endurance is so demanding, I put metal shoes on a few of our many horses. I rode a BLM mustang with the toughest feet ever, and tried to keep her barefoot, but having to condition as much as needed to get a horse fit for endurance on our terrain, I just wore her feet too short. I found that on many horses I could have taken barefoot otherwise; wear was the biggest issue. If I were just packing or trail riding in the mountains, I’d probably keep them all barefoot and boot when needed.”