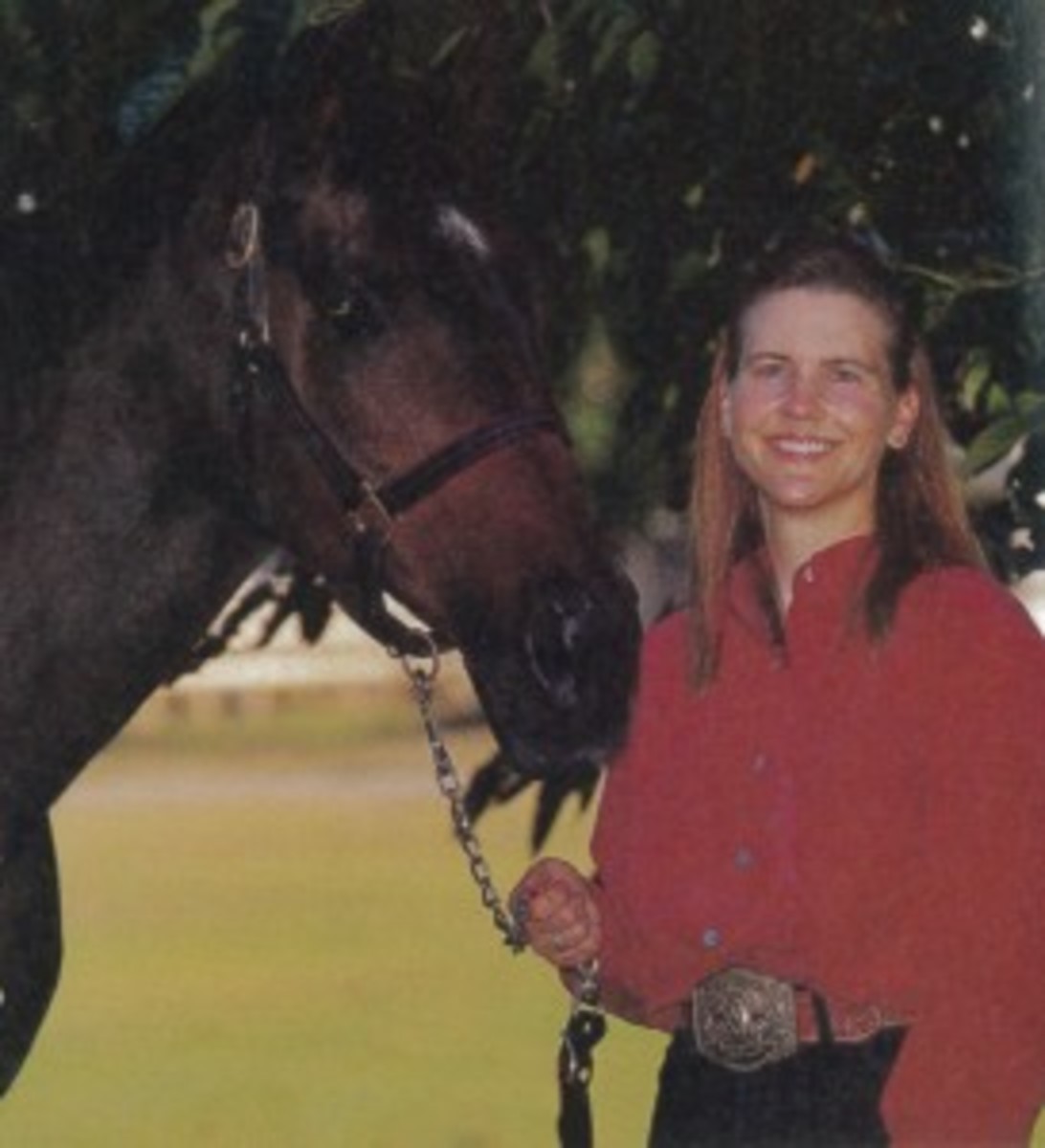

Sometimes solving a medical problem is like solving a puzzle. That was certainly the case for my 21-year-old grade gelding, Cavalier, and me. After a routine vaccination administered by a vet, “Cav” suffered an injection-site infection that drained his health and my resources. My gelding endured agonizing treatments for two-and-a-half months because of one critical piece missing from a diagnostic puzzle. It took a second opinion, a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease, and aggressive care to save him.

By sharing my tale of Cav’s Cushing’s disease diagnosis, I hope to keep you and your horse from ever enduring this sort of nightmare.

A Hard, Angry Lump

Wednesday, May 7 – The mystery begins. Just days after the local vet gives Cavalier a 5-way vaccination, there’s a hard, baseball-sized bump at the injection site. Cav’s neck is so stiff that I hang a hay bag at shoulder level, just so he can eat. On the vet’s telephoned recommendations, I begin several days of applying hot compresses to the injection site. I also administer two grams of bute with a balling gun to control the fever, which spikes to 103 degrees.

Tuesday, May 13 – The vet arrives and punctures the lump. A geyser of foul-smelling fluid gushes out. He prescribes a powder antibiotic twice daily, mixed with applesauce and administered from a drenching gun, and has me apply a topical salve to reduce the swelling. Relieved, I figure Cav’s on the road to recovery.

Wednesday, May 14 – A nasty surprise. Cav’s chest is enormous and filled with fluid. The lump is large and his fever rages. I call the vet out again and he cuts an inch-long slit in the lump for drainage, and tells me to flush it with hydrogen peroxide. He prescribes a diuretic powder to reduce the chest fluid and orders blood work.

Friday, May 16 – Cav’s chest fluid is almost gone, but the neck lump still oozes. He’s lost a lot of weight, and retains a long, thick winter coat. He’s been shedding out late for the past couple of springs, but I’ve never seen his coat this heavy.

Monday, May 19 – A week of medication hasn’t solved the infection. Over the phone, the vet prescribes a second antibiotic and Granulex topical spray to avert proud flesh. I begin twice-daily penicillin injections into Cav’s rump muscles, alternating sides. The blood panel results don’t reveal anything significant regarding the infection.

Friday, May 30 – Incredibly, the penicillin hasn’t helped. I’m distraught that the infection hasn’t responded to anything we’ve tried. I swab the pus and take a sample to the vet’s clinic for analysis. In the meantime, he prescribes yet another antibiotic. I’m still using bute for his fever and flushing the hole multiple times per day.

Tuesday, June 3 – Culture results show three different bugs at work in the infection. The vet prescribes a fourth antibiotic to combat all three. I’m beginning to feel there’s no cure, and worry the twice-daily injections could lead to another infection. I kick myself for having sold my horse trailer the year before, a move that now complicates my second-opinion options.

Friday, June 6 – Cav’s neck is sore and bruised from the flushing process. He’s endured multiple injections, pills, pastes, flushings, and fevers for weeks. His coat is yaklike, and his neck and left shoulder are scalded bald by the oozing infection and various treatments. His ribs protrude despite the fact that he’s kept a decent appetite.

Wednesday, June 11 – I continue doggedly with treatment. I’ve been making morning and evening trips to the barn every day for weeks, and spending hours with Cav each time out. Yet there’s been no real progress. In horror, I begin to wonder if I may have to put him down.

Thursday, June 12 – I decide we need to help beyond the never-ending cycle of phone messages and antibiotics. I ask an acquaintance with a trailer for help, and call the Loomis Basin Veterinary Clinic, about an hour’s drive away.

Wednesday, June 18 – At the clinic, Dr. Kim Sprayberry, an internal medicine specialist, sonograms Cav’s infection site and detects extensive “channeling” (pathways created by the infection) throughout the muscle. She draws blood for analysis and cultures the infectious ooze, then advises me to stop the antibiotic injections and target the infection site directly. She formulates a system of flushing the channels through a four-inch-long canula (a narrow metal tube), using Betadine solution and sterile saline instead of hydrogen peroxide. Cav remains at the clinic for two days so staff members can better establish paths for the canula, and flush the pus=filled channels several times per day.

Thursday, June 19 – Dr. Sprayberry tests Cav for Equine Cushing’s Syndrome while he’s at the clinic (it’s a two-day procedure). His long coat, advanced age, frequent urination, and ongoing infection are all symptoms of a “Cushing’s Horse.”

The Cause Uncovered

Friday, June 20 – I retrieve Cav from the clinic. His Cushing’s test is positive-the missing clue! Cushing’s horses are highly susceptible to infections and usually unable to fight them off. Dr. Sprayberry advises pergolide as our best option to deal with the Cushing’s, and encourages me to shop for the best price via the Internet. I return home armed with the canula, Betadine solution, antibiotic ointment, and instructions to make another appointment if the lump and opening aren’t better in a week.

Thursday, June 26 – The canula has become Cav’s worst enemy. Fed up with balling guns, drenching guns, syringes, needles, and thermometers, he views the canula’s probing of is sore spot as the last straw. He struggles so frantically I lose my hold, and the entire canula disappears down into his neck. More pushing on his flesh produces its tip, and I learn to tie string to it.

Tuesday, July 1 – We return to the clinic, where Cav spends the night. The next morning, surgeon Dr. Tom Yarbough will make a larger cut for better access to the channels.

Wednesday, July 2 – The bottle of pergolide arrives in the mail, and I take it along as I retrieve Cav. I give him his first .5 cc does of pergolide. I bring him home with instructions to continue flushing the channels using the Betadine/sterile saline and the full length of my latex-gloved finger.

Wednesday, July 9 – The end is finally in sight. The cavern in Cav’s neck is closing from the inside, and hasn’t produced pus since it was opened by the surgeon and the pergolide treatment began. His long coat is already shedding by the handfuls, and a short, shiny coat is peeking from underneath. There’s no need for bute, and Cav’s spirits are up.

Monday, July 28 – Only a faint scar and a wrinkle in the skin remain. I give him the pergolide every day, literally only a drop in the corner of his mouth, which he tolerates without being haltered. His coat is still shedding dramatically. He remains in good spirits, and has gained back some weight. I ride him for the first time since early May-and heave a heartfelt sight of relief.

Symptoms of Cushing’s Disease:

- Failure to shed the coat, which becomes long and shaggy.

- Increased thirst and frequency or urination.

- Increased or decreased sweating.

- Laminitis.

- Energy loss.

- Increased parasite load.

- Suppressed or abnormal estrous cycles in mares.

- Sometime a reduction in muscle mass, especially over the topline, and a tendency toward pot belly.

- Increased appetite despite apparent weight loss.

- Chronic or persistent infections. Due to increased production of cortisol, the immune system becomes depressed, leaving the horse vulnerable to infections. Note: A special blood test is required to diagnose Cushing’s; a normal blood panel will not reveal the disease.

Treatment and Management

- Talk to your vet about an appropriate medication, typically pergolide or cyproheptadine.

- Help regulate your horse’s temperature. Since Cushing’s disease makes it hard for your horse to stay cool in warm weather and warm in cool weather, blanket him in the winter as necessary, and body-clip him in the summer if necessary. Be sure he has shade, shelter, and access to fresh water.

- Limit grass exposure. Because Cushing’s increases your horse’s chance of laminitis, limit or stop his exposure to lush, spring grass-especially if he has a history of laminitis.

- Keep him vaccinated and dewormed to help boost his sagging immune system.

- Keep up dental work. Regular dental care can help minimize the chance of mouth infections and decreased physical condition.

- Maintain good foot care. Have your horse shod or timed every five to six weeks, keep his feet clean, and provide him with soft, level ground-free of rocks and holes-to minimize hoof abscesses.

- Adjust his diet. A Cushing’s horse has difficulty digesting carbohydrates. Use a top-quality, lower-carbohydrate feed formulated for senior horses.

Equine Cushing’s Syndrome (ECS) Facts

If you have an older horse, brush up on the basics of Equine Cushing’s Syndrome. ECS is a condition in which the horse’s adrenal gland is over-stimulated to produce the steroid cortisol. This is commonly due to over-production of (adrenocorticotropic hormone) ACTH, a chemical messenger (produced in the pituitary gland) that stimulates the adrenal gland. Cushing’s can be triggered by excess steroid medication.

The disease can occur in horses as young as seven, but most often strikes those in their late teens or 20s. In one study, 10 of 13 horses over the age of 20 showed at least sub-clinical Cushing’s-type symptoms. Cushing’s is twice as common in mares as it is in geldings or stallions.