Your gelding is dull and depressed. You pull out your thermometer, and discover he has a fever of 106 degrees—no wonder he feels crummy. You quickly call your vet. “My horse is really sick,” you tell her. “We did have a new horse arrive at the barn yesterday, but it seemed perfectly healthy when it moved in. And that horse is in a stall that’s clear across the aisleway from mine.”

Your vet suggests you isolate both the new horse and your gelding in a quarantine area. She tells you to start taking and recording temperatures of every horse on the property, and to isolate any that have a temperature of 102 or more. Meanwhile, she heads to the barn. “Your horse could have the flu,” she explains. “And if he does, we need to take it seriously, before it spreads like wildfire. Even though the horses are all vaccinated, they could easily become ill.”

“Why the flu?” you wonder. “Aren’t there lots of other viruses out there? And if it is the flu, where could it have come from? What can I do to help my horse feel better? And why do I even bother to vaccinate if it isn’t going to help?”

I’m going to answer all of those questions and more. I’ll help you understand what influenza looks like, and why an outbreak can be so scary. We’ll talk about the reasons why equine influenza has been making headlines in recent years, and will help you choose the best vaccine to help prevent your horse from falling victim to this devastating virus.

Flu Facts

With all the news about equine herpes virus (EHV) in recent years, influenza may seem to have faded into the background. In reality, equine influenza can have even more serious and far-reaching consequences than EHV. A 2007 outbreak in Australia affected over 40,000 horses and shut down the horse industry in that country for months.

As international equine travel grows, so does the spread of influenza. In 1995, there were 517 international equine events. By 2012, 3,200 recorded competitions required that horses travel to different countries. This widespread international travel opens the door for spread of infectious diseases, and influenza is one of the most frightening. This virus has been identified in every country of the world except Iceland and New Zealand, making it a worldwide concern.

Don’t take this to mean that your horse is safe because he’s not an international competitor or a big traveler. He’s just as vulnerable at a local level, including on your own property. You’ll soon see why.

Influenza is a single-strand RNA virus, meaning it’s made up of a single chain of genetic material. This type of virus is known for its ability to mutate rapidly. Thus, the virus changes all the time. This phenomenon is known as “antigenic drift.”

Why does antigenic drift matter? Your horse’s ability to fight off a virus typically depends on prior exposure to some form of that virus— either by getting sick or by being vaccinated. His immunity will become less effective if he’s exposed to an altered form of virus. This feature of influenza not only means outbreaks can occur in groups of horses with prior exposure, but also that vaccinations can become less and less effective over time.

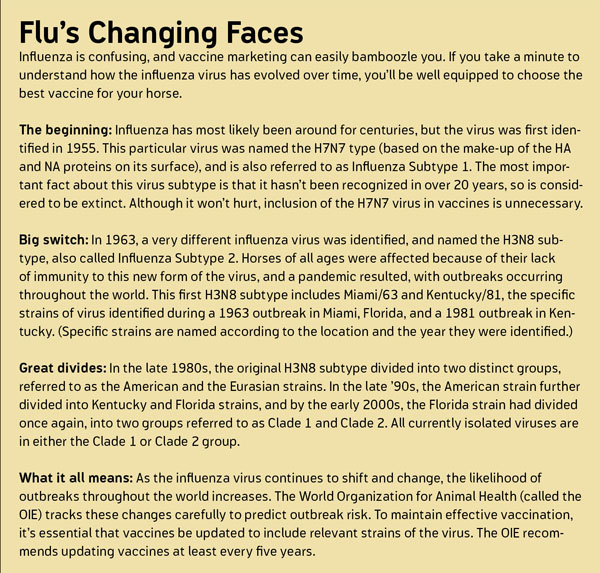

The virus has two large proteins attached to its surface: haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). The makeups of these proteins are used to name different subtypes of the virus, such as H7N7 (subtype 1) and H3N8 (subtype 2). The HA protein is most important. It’s this protein that allows the virus to enter and exit the horse’s cells to cause disease. HA is also what your horse’s antibodies recognize when they attack the virus.

Now let’s answer your questions about the scenario we described above, and learn what steps you can take to help protect your horse.

Flu FAQs

Why influenza? Aren’t there a lot of viruses that can cause my horse to have a fever?

While it’s true that many different viruses can cause your horse to spike a fever, a temperature reading as high as 106 puts influenza right on top of the suspicion list. It’s rare for other viruses to cause a fever spike that high. His fever may last as long as three days, when he’ll also be dull, depressed, and off his feed. You may see enlargement of the lymph nodes between his lower jaws, and his legs might swell. He’ll develop a nasal discharge and begin to cough. The influenza virus wreaks havoc on your horse’s airways, causing the cough that accompanies this disease to be dry, deep, and severe. It can persist for weeks. This severe, persistent cough is one of the reasons why influenza can be such a devastating disease. A horse with a serious case of flu can easily miss months of work.

Wouldn’t my horse have to be exposed to a sick horse to get the flu?

A horse that’s recovering from influenza will continue to shed the virus for anywhere from seven to 10 days after he’s no longer showing signs. And a vaccinated horse, or horse with natural immunity from a previous case of flu, can become infected, show no signs of disease—yet still shed the virus. That means it’s entirely possible for your horse to get the flu from another horse that appears perfectly healthy.

If your horse gets sick with the flu, he’ll have natural immunity that lasts a year or more. Vaccinations are somewhat less effective at producing immunity against the virus, depending on the specific vaccine used. With some of the older killed-virus vaccines, immunity begins to wane as early as three months following vaccination. When your horse is partially immune, he’s most likely to develop a “subclinical infection,” meaning he’s infected (and shedding virus) without being sick—presenting a huge risk to other horses, and leading to potential outbreaks.

How could my horse have contracted the virus from a horse stabled clear across the barn aisle?

Influenza is most likely to be spread via aerosol transmission. It hitches a ride on mucus expelled into the air when a horse carrying the virus coughs or sneezes. And a single cough can spread the virus as far as 50 yards! It’s also possible for the virus to be spread indirectly, via cleaning implements or handlers. Surprisingly, the influenza virus can be quite hardy too, remaining infective for as long as two days on an object, like a bucket or manure fork, and for as long as three days in water. Shared water sources present a major risk for transmission of this virus.

Even if the new horse did bring a virus to the barn, wouldn’t it take longer than a day for my horse to get sick?

The incubation period for influenza is very short. Your horse could begin to show symptoms of this disease anywhere between 24 hours and three days after being exposed to the virus. This feature of the disease is one of the reasons why outbreaks are so common once the virus strikes. Your horse could begin showing signs of the disease (and spread the virus to others) before you even know it’s in the barn or on the show grounds.

My horse is vaccinated against influenza—shouldn’t that protect him from the disease?

Vaccination against influenza is tricky. And when it comes to influenza vaccines, all are not created equal. You must consider three things when it comes to influenza vaccination: type of vaccine, route of administration, and the strains of virus included in the vaccine.

Influenza vaccinations can be killed (made up from a virus, or virus particle, that’s been completely inactivated), modified live (a virus that’s been altered to be non-infective but not completely killed), or vectored (a portion of the virus is injected into a living, but non-infective host virus). In general, killed-type vaccinations have the shortest duration and only stimulate an antibody response. Both modified-live and vectored vaccines have longer durations and stimulate both an antibody response and a non-specific (cellular) response, so are typically more effective.

Vaccines can be administered either in the muscle (IM) or through a tube up the nose (IN). IN vaccinations offer the advantage of stimulating an immune response in your horse’s nasal passages, where the flu virus enters his body. They may be more effective, but also can cause behavioral problems because many horses resent the “tube-up-the-nose” administration.

Finally, it’s critical that the strain of virus included in the vaccine be relevant (still circulating). For example, many older vaccines still contain the H7N7 virus strain, which hasn’t been identified in over 20 years. There’s really no reason to vaccinate your horse with this strain of the influenza virus. Instead, look for a vaccine that contains strains currently circulating, such as the H3N8 Florida strains. (For details on the relevance of different strains of influenza virus, refer to the sidebar.)

Although most available vaccines do offer some degree of protection, some are clearly more effective than others. By choosing a more effective vaccine, you reduce the risk that your horse will get sick, or that he’ll contract the virus without showing signs (putting other horses more at risk). Talk to your veterinarian about the best vaccine for your horse, and vaccinate every six months for best protection.

How can I tell if my horse really has the flu? Even though my horse’s fever is high, he still could have a different virus, right?

It’s true that many different viruses can cause a fever. Although treatment might not change, identifying the specific virus can be very helpful for managing an outbreak. If influenza is truly the cause, risk of outbreak is particularly high due to the short incubation period and potential for rapid spread.

The best test for diagnosing influenza is called a “polymerase chain reaction” (or PCR) performed on a nasal swab. This test identifies actual genetic material from the virus, providing proof that the virus is present. It’s quite accurate, and results are generally available within 24 hours.

Your vet also may suggest checking your horse’s blood for antibodies (called serology testing). For this test to be meaningful, it should be performed when the horse first shows signs, and then repeated two weeks later to determine if there’s been an increase in the number of antibodies in your horse’s blood. This increase would be expected with an active infection. Be aware that a single sample only tells you if the horse has been exposed to the influenza virus (possibly even from being vaccinated), not if he actually had the flu. The major disadvantage of this test is that results of the second test won’t be available until an outbreak is well underway.

My horse is really miserable. Is there anything I can do to make him feel better?

Because influenza is a virus, it won’t respond to antibiotics. The best you can do is to take steps to manage your horse’s symptoms while the virus runs its course. You’ll need to take his temperature twice a day, and if it’s very high, your vet is likely to suggest anti-inflammatory medications such as flunixin meglumine (Banamine) as needed to control his fever. Cold hosing, ice baths, or alcohol washes might also help. If your horse is very ill and refusing to eat or drink, oral or intravenous fluids can help to keep him hydrated.

If your horse’s fever lasts longer than three days, or his nasal discharge becomes very thick and discolored, it’s possible he’s developed a secondary bacterial infection. If this occurs, antibiotics might be recommended.

Because of the damage the influenza virus causes to your horse’s respiratory tract, a long period of rest probably will be necessary. In general, your horse will need a week off work for every day he’s had a fever. Expect your horse’s complete recovery from a bad case of the flu to take anywhere from six weeks to several months.

If influenza is confirmed, what steps should we take to prevent spread?

Because the incubation period for influenza is so short, it’s critical to identify infected horses as quickly as possible by taking temperatures of every horse on the property twice each day. As soon as a fever over 102F is detected, that horse should be moved to isolation.

Isolation of any infected or exposed horse is the most important step to minimize the severity of an outbreak. It’s best if isolation is in a completely separate barn located at least 50 yards from other horses. The isolation facility should have its own equipment for stall cleaning and foot baths with disinfectant in front of every stall. Handlers should wear gloves or wash hands thoroughly after working with isolated horses, and work in the isolation area should be performed only after other non-impacted horses are cared for.

Remember that an infected horse can shed virus for as long as 10 days after he’s no longer showing signs of disease. It’s best if he stays isolated for a minimum of 21 days to ensure that he’ll no longer be a risk to other horses. And to prevent spread to other locations, the facility should remain isolated for the same period of time after the last sign in the last horse.

If the outbreak is identified early, you may be advised to vaccinate other horses in the barn. Specifically, the intranasal influenza vaccine can provide some degree of protection as early as five days after administration, even for a horse that’s never been vaccinated before.

As with most infectious diseases, prevention is always the best strategy. I recommend that you require proof of influenza vaccination for any new horse, and isolate all newcomers for a minimum of 14 days.