If I’ve heard it once, I’ve heard it a thousand times.

“Bet you’ve never seen anything like this one, Doc. My horses always have the weirdest problems.” Guess what? I’ve probably seen it. In fact, after nearly 25 years in practice, I think I’ve seen just about everything—twice!

[READ: KEEP YOUR HORSE IN A VET FRIENDLY BARN]

Then there are those “other things.” The really weird cases. The ones I’d never seen before, and hope to never see again. These are the horses we talk about in the truck for years, the stories we tell at office Christmas parties, and the people I’ll never forget. I’m going to tell you about seven “can you believe it??” episodes—the most amazing things I’ve ever seen—and what they offer as takeaway lessons for anyone with a horse.

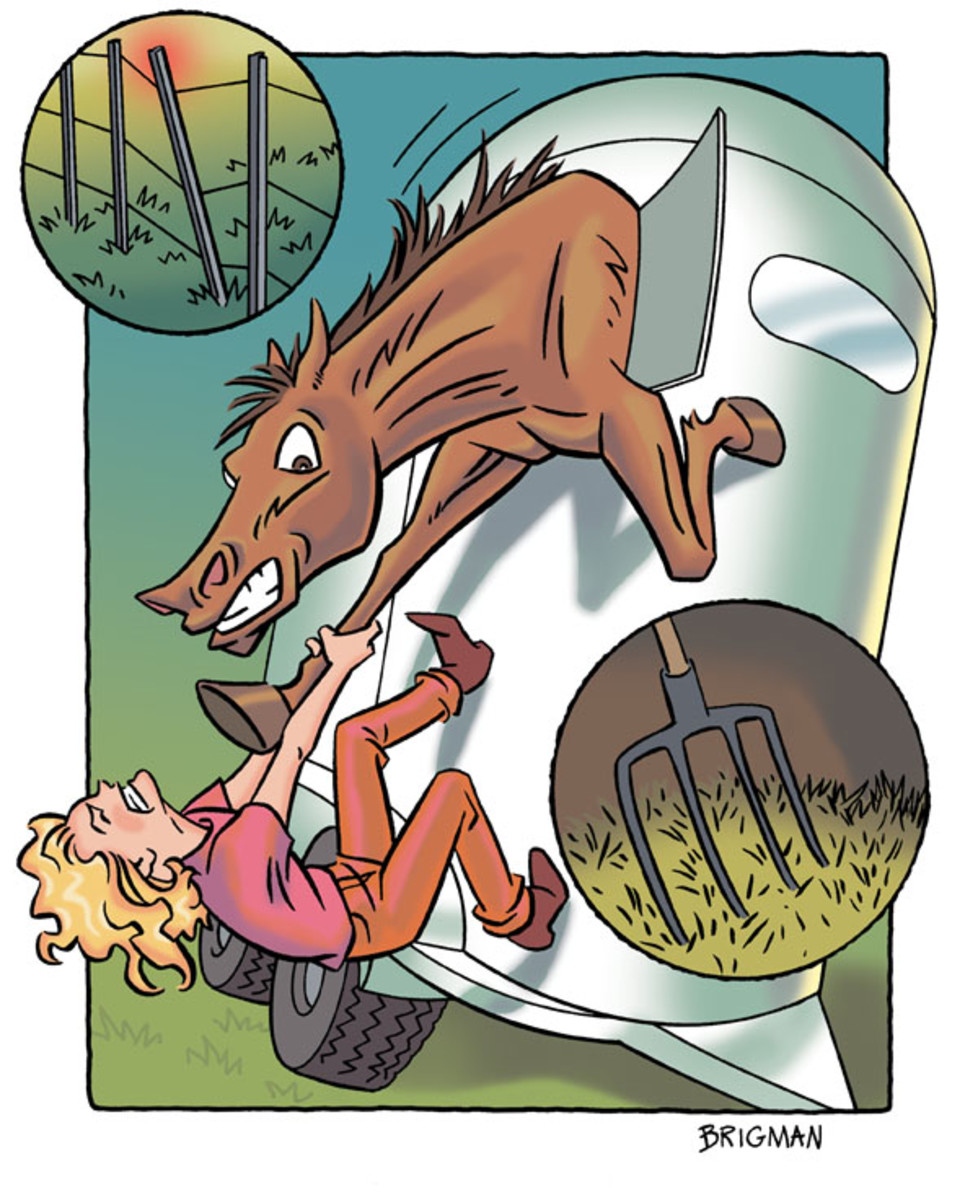

Case #1: Trailer Delivery

The call came when I was at the office, and the caller was panic-stricken. “We were loading my horse, and she tried to jump out through the window up front. Now she’s trapped in the window. We need help right away.”

Rarely do I grab my keys and race for the truck, but this time I did. As I sped out our driveway, I called my associate veterinarian, thinking she might be closer to the client’s farm than I was. “911,” I told her. “This one sounds like a real emergency—drop what you’re doing and run.”

When I reached my client’s farm, I couldn’t believe my eyes. There was a 1,400-pound Friesian mare, hanging from a 24-by-36-inch trailer window. Her head was on the pavement, and her hips were still inside the trailer as she hung suspended from the window. My associate had beaten me to the scene, immediately administering anesthesia to keep the mare from struggling, but how were we going to get her out?

We were lucky. I was able to draw from many years of delivering foals, and we set out to “deliver” the mare from the trailer window. By manipulating her hips in just the right way, we got her dislodged, and out she slithered—onto the pavement. Even more amazing? Not an injury in sight. When she woke up from her anesthesia, we administered IV fluids and some anti-inflammatory medications—and that mare acted like nothing had happened.

Lesson learned: NEVER, EVER load or let your horse stand in the trailer with the front window open if you’re not there to guard it.

Case #2: An Extra Rectum?

My client, who’d recently returned from a horse show, called to have me check on a wound her horse had sustained while on the road. “He drove a manure fork into his rear end when he was in the grooming stall,” she explained, “It looks like he has an extra rectum, and we want you to check him out.”

Expecting to find a typical puncture-type wound around the horse’s hindquarters, I lifted up his tail to see a small tag of gauze immediately above his rectum. My client told me that the wound had bled quite a bit, but that the vet who treated him thought the packing should be removed this week. Remembering the wise old veterinarian who once told me, “the Lord hates a coward,” I took hold of that tag of gauze and pulled…and pulled…and pulled. I tugged at least 12 feet of gauze out of that hole, and when I was done it looked exactly like my client had described: The horse appeared to have an extra rectum.

Somehow, he’d managed to drive the tine of a plastic manure fork straight into his rear end, making a hole that was at least 12 inches deep. The good news? With the minor complication of an impaction colic that resolved with fluid therapy, that wound healed up in no time, and the gelding was as good as new.

Lesson learned: Don’t leave those brooms and forks in the manure buckets at the back of your grooming stalls when a horse is cross-tied. In fact, it’s best if you keep cleaning instruments away from your horses altogether—but that’s a story for another day.

[READ: WOUND-CARE GUIDE]

Case #3: Just Another Colic—Not!

It started out like just any other colic. The horse was pawing and looking at his sides. His owner reported that his signs were pretty mild, but she wanted a visit anyway. When I arrived at the farm, her horse seemed mildly uncomfortable. His heart rate wasn’t terribly high, he had normal gut sounds, but he just kept looking at his side. His rectal exam was unremarkable, so I administered a dose of Banamine, thinking he’d be better soon.

He didn’t get worse, but he really didn’t get any better, either. His owner and her friends told me that he just kept staring at his sides. In fact, they wondered if he wasn’t staring at his sheath. “What the heck,” I thought, “I might as well clean his sheath and see if something’s bothering him there.”

That’s when things got weird. When I pulled my hand out of his sheath, my glove was covered in…maggots. That’s right. This gelding’s colic episode was due to maggots in his sheath. A thorough cleaning was all it took to resolve his symptoms—and we never found out why the maggots had decided to take up residence.

Lesson learned: Listen to the horse—and to those who care for him and know him well. In this case, the horse was trying to tell us what was wrong by staring at his sheath. It’s a good thing that his owner paid attention to what her horse was saying—and I’m happy that I listened to them both. I’ll also be thrilled if I never experience sheath maggots again.

Case #4: Through and Through

I was called out to see a puncture wound on an older horse. Apparently, he’d gotten into a battle with a T-post, and the T-post won. Puncture wounds are common in our practice, and T-posts are to blame in way too many cases. Many times these wounds are big and deep. I’ve seen them lots of times.

But never quite like this. When I arrived, I found the horse with a puncture that was several inches in diameter—extending up through his flank, and out the other side. That’s right. When I looked down into the wound from the top of the horse’s hindquarters, I could see the ground on the other side.

The most amazing thing about this wound was that the post had managed to miss all vital structures. It bypassed the stifle joint and all of its associated ligaments, saving the horse from severe long-term lameness. The post also narrowly avoided entering his abdominal cavity—where death would have been a likely outcome. In fact, with minimal treatment, that wound healed just fine.

Lesson learned: If you have T-posts on your property, cap them. Better yet—avoid them altogether.

[READ: LUMPS & BUMPS GUIDE]

Case #5: A Dime a Dozen

I live and practice in Oregon, where sole abscesses are one of the most common things we see. It’s not unusual for me to see and treat several abscesses every week, if not several every day.

On first inspection, this horse looked no different. He had sudden and severe onset of lameness, just as abscesses often produce. Yet when I first examined him and couldn’t detect a strong digital pulse in his foot—something I’d expect with a typical abscess—a little voice at the back of my head said “something isn’t right.” I was relieved when I opened a huge pus pocket at his toe. “Soak the foot and keep it wrapped,” I told his owner. “He should be better in just a day or two.”

But that was not to be. He didn’t get better; he got worse, and he continued to drain pus from his foot. Radiographs didn’t tell us much. His coffin bone looked normal. And his foot was strangely cold, still with no digital pulse. When he didn’t improve at all after several weeks, we referred him to a specialist who performed a venogram—a contrast study to help evaluate the blood supply to his foot.

We learned that all of that blood supply was gone. Something had happened to this horse that caused the blood vessels in his foot to completely shut down—and nothing could be done. That horse lost his life after what seemed like a simple abscess, and we’ll never know what really happened.

Lesson learned: Things aren’t always what they seem. And when something tells you “this isn’t right,” listen to that voice.

Case #6: Just Keep Looking

This big gelding started out as a pretty typical trauma case. His left front leg was hot and swollen, and he was dragging his toe along the ground when he tried to take a step. He could bear weight normally, though, so a serious injury, like a fracture, seemed unlikely.

He responded slowly to initial treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, ice, and hosing. The lameness resolved, and swelling was almost gone after several weeks. Then it reappeared.

Radiographs of the leg ruled out an underlying fracture, and he was referred to our local university for an ultrasound of the area. They didn’t see much beyond fluid in the surrounding tissues, and a possible injury to one of the ligaments in his shoulder. We figured he must have injured it a second time. Thinking he was hurting himself when he got up and down to roll, we concluded it was best to tie him in his stall for another period of rest.

Instead of getting better, the swelling increased and developed quite a bit of heat. With the thought that he was developing a cellulitis (infection in the tissues underlying the skin) secondary to the chronic swelling, we administered antibiotics. That seemed to do the trick.

But not for long. A month later, it started all over again, this time with even more swelling than ever before. Another trip to the university…another ultrasound…still no answer to the swelling. Then, one day when it opened and drained, a large abscess pocket was revealed to be sitting deep beneath his shoulder. The drainage eventually produced a 2-inch-long sliver of wood. This poor horse had somehow managed to drive a piece of wood deep into his armpit, where it created a giant abscess that couldn’t be seen on an exam, or even detected with radiographs or ultrasound. Once his body finally decided to get rid of the offensive foreign body, the swelling resolved and he never had another problem.

Lesson learned: Science may not have all the answers; often, the equine body itself knows best what to do. And if something doesn’t seem quite right, it probably isn’t. Don’t give up until you find the answer.

[READ: MEDS OR MANAGEMENT]

Case #7: Another Day…

Remember that pitchfork? This call came early in the morning, from the frantic husband of a veterinary surgeon who lived down the road from my house. “I was feeding the horses, and I found my wife’s gelding down in the stall, with a pitchfork handle sticking out of his abdomen. I think he’s dead.” Sure enough, that poor horse was dead—after having decided to play with the cleaning implement that he found leaning against his stall door.

Lesson learned: See Case #2; what’s convenient for you can be deadly for your horse. Be careful with those cleaning implements, and make it a rule to never leave one where your horse can get hold of it when you’re not looking.