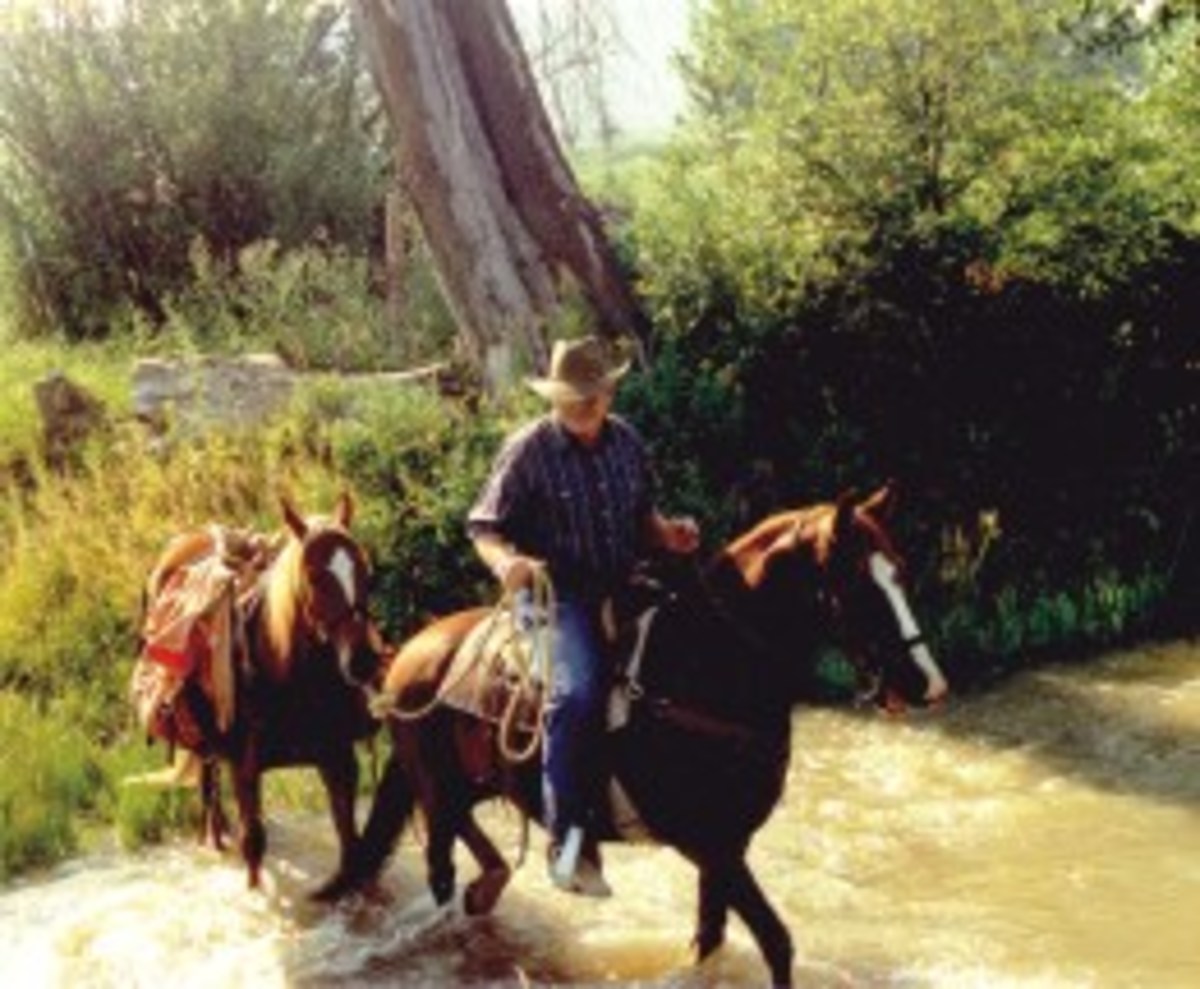

Through a place in south-central Montana we call the “gorge,” where the trail is a ledge between a cliff rising vertically on one side and a frothing river below on the other, I recently watched a man descend on horseback leading a pack string followed by several riders. Though the trail through this stretch is good, many riders find it intimidating; the river’s roar and the fine mist of spray keeps the rocky trail wet. It was clear, however, that passing through here was old hat to this man. He held a slim pair of leather split reins in his left hand in light contact with the horse’s bit, and the lead rope of the front pack horse in his right.

As the group approached me, their leader suddenly stopped, and with a movement of his left hand so slight you could scarcely notice it, reined the horse broadside on the trail facing the drop-off to the river. For a moment I thought something was wrong, but the man wanted merely to take a photo of the group behind him. He laid the pack horse’s lead rope over the pommel of his saddle, grabbed the camera that hung around his neck, aimed it with his right hand, snapped the photo, and dropped the camera back into place. Finally he picked up the lead rope again, and with a subtle touch of the rein to the right side of the horse’s neck, deftly turned the animal left down the trail again.

What I’d watched was a traditional backcountry horse, a horse with a neck rein so complete and so subtle that a second hand was never needed on the reins, even on a treacherous trail. I respect all styles of riding disciplines and training, but for me the “complete” trail horse neck reins. The “using” horse of the mountain man, explorer, and cowboy traditionally neck reined, thus freeing one hand to carry a long rifle or to rope a steer.

The neck rein – that is, “push” pressure applied to a horse’s neck opposite the side in which you’re turning – is equally desirable for today’s trail rider. It leaves one hand free to pony a pack horse, fend off from the tree your horse scrapes by too closely, operate a camera or pair of binoculars, or hang on in an emergency while still guiding the horse.

Neck reining also makes possible such advanced backcountry skills as dragging a dead snag of firewood back to camp or pulling a companion’s horse out of a bog, when one free hand is needed to dally a rope around the saddle horn. Swapping reins from one hand to the other eases fatigue on a long ride and gives you a free hand on whichever side of your horse it’s most needed.

A horse with a finished neck rein responds to the slightest touch of rein on neck and is guided by the smallest movement of your hand in the direction you wish to go. The relaxed harmony between you and the horse makes riding more enjoyable. One ride on such a horse is likely to spoil you, but the good news is that training a horse to neck rein is relatively easy. I begin teaching it on the very first ride, but most older horses from other disciplines can readily pick it up. Here’s how.

(First, a distinction: I’m teaching the neck rein, not the sport of reining. Training a horse for reining competition is a specialized activity, and successful reining trainers have their own particular approaches.)

Your Equipment

For starting most young horses, I prefer a snaffle bit, but the methods outlined here will work with a hackamore, as well. The mecate-type reins currently in vogue are fine if you’re extremely adept at using them. I find, however, that eliminating any extra length and clutter makes my cues to the horse more straightforward, so I prefer a single looped rein of braided leather. And, for reasons we’ll discuss later, I like one that’s relatively short.

However, we’ll strive to eventually switch to split (two piece) leather reins, because they’re not only the most comfortable in a single hand, but the safest. I teach students in my clinics to avoid anything that can form a loop that might snag an arm or leg in a wreck, which can lead to dangerous complications. Two-piece, non-looping reins are less likely to snag.

Your Cues

Easy neck-rein training is based on three cues given simultaneously to your horse every time you turn him from the very beginning of training. First, whether with bit or bosal, your horse must already know how to yield laterally (to the side) with direct-rein pressure. Direct-rein pressure is that placed on the bit directly from your hand: With a rein in each hand, you apply left-rein pressure for a turn to the left and right-rein pressure for a turn to the right. If your horse lacks this training, go back to basics, consulting a reputable trainer or clinician if you need help.

For convenience, I’ll refer to the side of the horse opposite from the direction you wish to turn (the side receiving the leg cue and neck rein) as the “off” side. Think of off-side cues as those that “push” your horse into the turn, and the inside, direct-rein cue as the one that “pulls” your horse the correct direction.

To teach your horse to neck rein, apply direct-rein pressure as you turn him, but do two other things, as well. When turning left, apply direct rein pressure on the left side, lay the rein on the right side of your horse’s neck, and give a leg cue on the right side approximately at the cinch line. Reverse these directions for a turn to the right.

Think about what we’re doing here. Your horse is associating not one but three cues with every turn. Consistency is key. When training your horse, use all three cues, even when you’re following another horse down a curvy trail through the trees when he’d turn with no cue at all. Be assertive with the leg cue. I often use spurs to allow a lighter touch and to better isolate my leg cues. Stay away from them, however, if you’re insecure and believe you may inadvertently clamp them against your horse if he spooks.

Soon, your horse will associate each of the three cues as reason in itself to turn, and you can begin eliminating one of the three, then two, until only the neck rein remains. Your first target for elimination is the direct rein, and you’ll do it gradually. For a while, you’ll still use a little as necessary. If you’ve chosen a short, single rein, you’ll find you can hold it in one hand with less slack on the side toward which you’re turning. Neck reining in that direction will also tug at the inside rein.

Later, with split reins, you’ll find a technique for holding one or more fingers between the reins allowing a slight tightening of the inside rein as you ask for a turn. Forget show-ring prohibitions against fingers between the reins and against switching hands! On the trail, you need only be concerned about safety (yours and your horse’s), comfort, and practicality.

Going One-Handed

But long before your horse masters the neck rein, you must discipline yourself to apply it consistently. As your horse progresses to the point where he needs little inside, direct rein, deliberately place whichever hand isn’t holding the reins into your vest or jacket pocket, or onto your hip. Then, in a corral or arena, take him through your normal riding routine – all the usual turns, stops, starts, and backs – using just one hand.

Be patient. If your horse hesitates to turn, give him some time to assimilate and respond to your cues. Neck rein very deliberately, with a firm leg cue on the off side, and reward with praise. You’ll have better control if you avoid holding the reins excessively high. Six inches or so above the base of the horse’s neck is about right.

As I’ve said, neck rein even when it seems unnecessary, when your horse is already turning in the direction you wish. If you live in the West, try riding off trail across sagebrush flats. Pick your way through the sagebrush, choosing your route by neck reining, rather than allowing your horse to choose the way.

Better yet, help a rancher move cattle across similar ground, which involves endless trips from side to side. After one good day following a herd of cattle, your horse will likely come home with a decent neck rein.

When teaching the neck rein, note that an older horse will likely be a tougher nut to crack than a younger one would be. If your older horse is accustomed to direct reining, particularly if leg cues are alien to him, you might have to go back to basics in a round-pen or similar enclosure. You might also need to enlist the help of a reputable trainer or clinician.

But every horse is different. Don’t assume you must make drastic changes. For instance, you probably won’t need to return to the bit with which he was direct reined. If your horse yields softly to direct inside pressure with the bit he’s used to, there’s no reason to change. He should respond to the same approach used with a younger horse.

As your neck-rein training progresses, you might find that your horse will choose to ignore the cue in tight situations where he tends to resist all rider cues. For instance, rather than crossing a particular trail obstacle – such as water – he might try to turn around, ignoring your neck-reining cues as you attempt to guide him forward. In these types of situations, first try the leg cue to reinforce your neck-rein cue. If your horse still resists, go ahead and return to direct reining, with a rein in each hand. Don’t feel a sense of defeat.

The canter, too, may be problematic at first. Your horse might’ve made the transition to neck reining just fine at the walk, running walk, or trot, only to seemingly forget it while cantering. If this is the case with your horse, take him into a round pen or similar enclosure. Canter him against the rail using only the correct neck rein and leg cue for the direction in which you’re turning. Then walk him to the center of the pen, neck rein him in the opposite direction, and again cue him into a canter. As he develops, cantering figure eights with only neck rein and leg cue – lead changes and all – will become smooth and easy.

Refinements

As mentioned, I strongly recommend an eventual switch to leather split reins for safety and hand comfort. Trail riding entails even more attention to worst-case scenarios than do other horse disciplines, because of likelihood that help could be far away in the event of an accident. All large loops are potentially dangerous.

To transition to split reins from a single rein, cross the reins at the pommel so that the left rein drapes on the right side of the saddle and the right rein drapes on the left side of the saddle. Place your hand or hands on both reins. Thus, you have the effect of a single rein, but the safety of split reins.

Throughout neck-rein training, strive for what I call “light rein” rather than “loose rein.” To me, “light rein” means enough slack that your horse moves freely and comfortably, just nudging toward the limits of the reins as his head telescopes forward with each stride.

To many today, “loose rein” means what old-timers called “belly in the rein.” That is, so much slack that the reins make large loops that hang below the horse’s shoulder. Such excessive rein results in two safety problems for the trail horse. First, flopping reins, especially heavy rope ones, are more likely to snag on something, such as a tree branch.

More important, loose reins make quick application of the “one-rein stop” nearly impossible. (See “Spook Control,” On-Trail Training, January/February ’05.) You better figure that if you round a bend and meet a bear, your horse will spook. And, he’ll have a couple of good hard jumps on you before you can pull him around, if you must reel in an excessive amount of loose rein.

How to Ruin a Neck Rein

It’s extremely easy to ruin a neck rein in a horse that already has one. When a guest rides one of our ranch geldings, I always explain that the horse has a finished neck rein, so please ride with only one hand. I point out that the horse will be confused if a rider uses the direct rein. I then demonstrate.

Often, however, the guest will find a slight hesitation in the horse’s response to a neck rein, because the horse is working to adjust to the different feel of a strange rider. The rider responds by reaching down with one hand and yanking the horse’s nose in the direction desired. A few instances of this will cause the horse to quickly “unlearn” his neck rein training. Why? A doubt has now been created in his mind about the first cue he’s received, so he waits for the direct pull.

Be consistent and patient, and that light, subtle, nearly imperceptible one-handed guidance for your horse awaits you a few miles down the trail. And, when I see you there, you’ll have a free hand with which to wave!

Dan Aadland (http://my.montana.net/draa) raises mountain bred Tennessee Walking Horses and gaited mules on his ranch in Montana. His most recent books are The Best of All Seasons, The Complete Trail Horse, and 101 Trail Riding Tips. Sketches from the Ranch: A Montana Memoir is now available in a new Bison Books edition.