I shouldn’t have ridden that day. I was tired. Real tired. I’d just hauled home to Paso Robles, California, from a circuit in Arizona. But I’m a trainer, and I had client horses to school.

It was mid-March of 2010. My assistant, Jana, worked a 9-year-old mare in the round pen for me before I stepped on, to get any “fresh” out. She’s a nice mare, always eager to please. But she’s also sensitive, what I’d call “feely.”

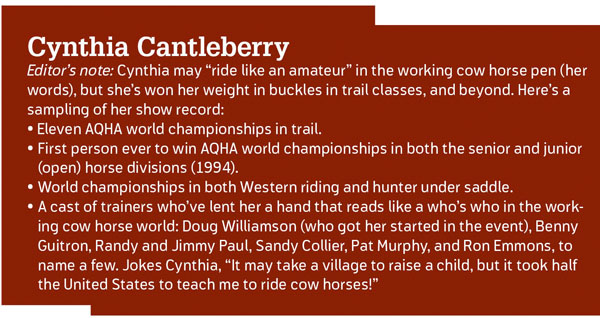

I hadn’t planned to ride her long; I just wanted to do a “status check” since she’d had a break while I was showing. She was good. I loped her over a few trail obstacles (trail is my specialty), gave her a pat, then loped her over to the rail and said, “whooooa.”

This mare has a real soft mouth, so I never have to pull. But before the “oooa” left my lips, she erupted with volcanic force, hurling herself over backward. I had no time to react. We crashed to the ground as one, the bulk of her weight atop my left leg; I could feel the saddle punch into my groin. I knew instantly I was hurt. I had no idea then how badly.

The 5 Percent

The mare scrambled off me and took off running, which caught Jana’s attention. The girl raced over, shocked, when she saw me on the ground; she hadn’t seen the horse flip.

“Call 9-1-1,” I said calmly. I wasn’t in any real pain but my body was telling me something wasn’t right. Jana responded, “Are you sure?” She’s a roper; they’re reluctant to take ambulance rides.

I was sure. I’d never before had a wreck. In fact, I’ve only been bucked off four or five times in 59 years of training. But having a 1,100-pound horse stab a saddle into your groin is no a small thing. “Just call 9-1-1,” I replied.

While awaiting the ambulance, we tried to figure out why the mare flipped. I ride her in a ring snaffle that has a “slobber strap,” a leather strip that connects the snaffle’s rings so they can’t slide through a horse’s mouth. I also had a German-type martingale on her. All we could figure is that she hooked her mouth on the slobber strap or martingale and panicked. We’ll never know.

The EMS guys gave me something that knocked me out on the way to the hospital. I woke briefly in the emergency room to find cow horse trainer Jimmy Stickler; his wife, Kim; and their kids by my bed. Jimmy was holding my hand, saying, “Cynnie, we love you.” I thought, “Oh, how sweet! But why’s he saying that?” I wasn’t in any pain. Jimmy’s not a guy who freely shares his emotions. But we’re close—when his mom died of cancer about 10 years ago, we adopted each other. (My husband, Red, died in 1999.)

I’d later learn that the mare’s weight had crushed my femoral artery, which is the major artery that runs from your groin down your inner leg. I was told only 5 percent of people with my injury survive the ambulance ride to the hospital. Of those survivors, only another 5 percent leave the hospital alive. Fortunately, I was blissfully unaware. Jimmy continued to hold my hand as I was wheeled into emergency surgery.

Surgeons implanted a stent into the injured artery, so blood could freely flow once more. Thanks to the fact that riding keeps me in good shape, I was able to head home in about a week. While I was recovering, Jimmy came to my barn three times a week to ride my horses and give customers lessons; he also took them to shows. Kim or one of my customers stayed with me at all times; I don’t think they trusted me to stay quiet!

My joy at being home was short lived. Kim took me to a follow-up doctor’s appointment for a CAT scan. Afterward, we had lunch. I started shaking and shivering uncontrollably. Kim rushed me to the hospital, where they pulled blood and started me on antibiotics, as a precaution. The shaking stopped, and otherwise I felt fine, so I was released and Kim drove me home. Not long after, my cell phone rang. It was the doctor; he’d gotten the blood-work results. “Get back to the hospital. Now.”

He said I had a raging infection. It turned out it was at a drain site in my abdomen. (The surgeons had to drain a great deal of blood before they could put in the stent.) Bacteria were taking over my body. Oddly, I still felt fine, and had no fever. Plus, it was cold and rainy. I said, “Can’t it wait until tomorrow?” He said, “NO!”

I was taken by ambulance to San Francisco, where a vascular surgeon cleaned out the infected areas, closed up the gaping drain hole, and started me on major antibiotics. Kim and my friend, Karen Gerfen, came with me; they never left my side.

Two days after the surgery, I felt pain for the first time. Bad pain. I pressed the “call nurse” button. The nurse came; she immediately called for the surgeon. The arteries at the drain-repair site were bleeding into my abdomen. Back I went for my third surgery. Fortunately, it would be my last…at least that year.

Upping the Ante

That was late March of 2010. I was back on a horse in May. It was as though I’d never stepped off. My customers made sure I rode the safest horse on the ranch, a Quarter Horse mare named Classy Reprint, owned by Joan Deregt. I felt no fear as I walked and jogged her around the ring; after nearly 60 years in the saddle (much of that as a pro), I knew mine had been a freak accident.

But I could tell by their faces that my “cheering section” lacked my confidence. After I guided the mare over a few trail obstacles, Joan’s daughter, Lauren, called out, “OK, that’s good. You can get off now!” I could see them all sigh with relief when my boots hit the ground.

I did a mental inventory after that ride: My left leg was numb. And weak; I had trouble lifting it to get into the saddle. But otherwise, I felt the same. Having had a doctor look me square in the eye and say, “You shouldn’t even be here,” I knew I was darn lucky.

I spent the rest of the summer building up strength by riding my trail and all-around horses…and being thankful I could ride. That fall, I started riding my working cow horse again. Sure, my claim to fame is in the trail ring, and I’m known for doing the all-around thing. But working cow horse is my thing, my hobby, the one riding-related event I do for myself. I love it.

I’m not one of the great ones—far from it. I ride at an amateur level, but have to show against the pros, since I’m a trainer. I don’t care. Cow horses are my passion. And I have a cool little horse on which to compete.

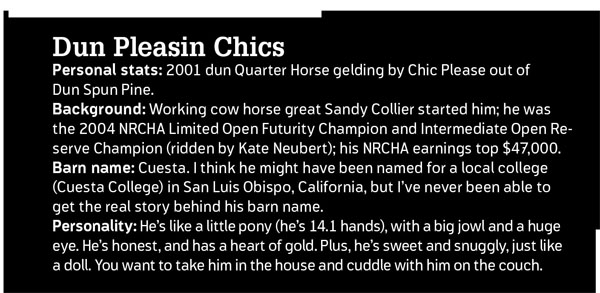

It was at Jimmy and Kim’s that I first saw Dun Pleasin Chics (see box on page 76). It was the fall of ’09. Their 10-year-old son, Tate, was loping him around, changing leads. I half-joked to Kim, “I bet I could ride that one!” Next thing I know, Kim had me on him. I loved “Cuesta,” but he was out of my price range. I figured he’d stay that way, but a short time later, his owner’s husband died, and she dispersed her herd. Cuesta was mine.

After the wreck, my residual numbness and weakness was most apparent when I went down the fence with a cow. I lacked the feel and timing I’d had before the accident. I had to grab the horn to stay on, something I’d never had to do. Oddly, doing so made me feel off balance until I got used to it. But I had no choice: If I didn’t grab the horn, I’d fall off.

With practice, I felt my timing and balance improve. I set my sights on the 2011 AQHA World Championship Show in November; Jimmy helped me get Cuesta qualified. It wouldn’t be my first time to show in the cow horse there, but it’d definitely be the most meaningful. Especially since you shouldn’t even be here kept echoing through my head.

At the World Show, Jimmy helped me prep, as did National Reined Cow Horse Association million-dollar rider Todd Crawford. I’d made Todd a deal some years back: “You help me get into the finals, and I’ll give you an Abbie Hunt bit.” (Those vintage bits, made by the late cowboy bit-maker, are sought-after items; my husband was a collector.) It turned out to be a lopsided deal: Todd always helped me. But I never made it into the finals, so he never got his bit.

Finally, I felt so bad that I surprised him with a bit. That tall, quiet cowboy with the slow smile nearly cried. For 2011, I upped the ante. I said, “If you get me into the top 10, I’ll put a pair of Ortega reins on that bit.” (Luis B. Ortega rawhide reins are also collectors’ items cherished by horsemen.) Guess what? Todd got his reins.

Came to Play

By our first go-round at the World Show, and with Jimmy and Todd’s help, Cuesta and I were ready. Our draw for the first go was a good one: We’d go 25th out of 53 competitors. We started with the “dry work” (reining) pattern. The gelding and I were mistake-free, and earned half-plus points on many of the maneuvers. There are five judges; the high and the low scores are dropped. We ended up with a 213.

Then came our cow work. We were game. The steer wasn’t: He came out and started bouncing off the walls like a pinball, refusing to even acknowledge us. Fortunately, the judges were great about leveling the cattle playing field—they’d whistle out a bad steer and send in a new one. When I heard the whistle, I was thrilled. I’d get another chance with another steer. Once the show crew got the bum steer out of the ring, a new one was sent in. And it came to play.

Cuesta and I “boxed” it at one end of the ring to demonstrate control (similar to cutting). After the required 50 seconds, it was time to run the steer down the fence. I didn’t know my little horse could run that fast. He was on fire! We turned it in both directions, then circled it up in the center of the ring. It was a spectacular run for us, earning a 222.5 total. We ended up sixth in the first go. The top 15 horses return for the finals. We were in!

We had a less-good draw in the final go-round: We were first to go. (In my 35 years of showing at the World, I’d never gone first, in any event, until this time.) No matter. I was thrilled to be there. Cuesta and I added even more plus-points to our dry work, scoring a 216. Our cow work had a sense of deja vu, in that we had another first-steer issue: When it came time to run him down the fence, he stopped, plopped down, and curled up like a napping dog. The judges whistled him out and gave us a new steer. He was straightfoward and we netted a solid 212, for a total of 428 points. That earned us seventh place—my first World Show working cow horse top-10 finish! Even better, it netted us third place in the intermediate open division (run concurrently, and based on earnings). So…two top-10 finishes. And, I shouldn’t even be here.

New Perspective

Afterward, it seemed as though everyone wanted to buy Cuesta. I guess they figured if he could pack around a (then) 68-year-old woman in the working cow horse, he could pack around anyone! But he’s not for sale. Nope, I want to qualify for the senior working cow horse at the World Show again this year. I think Jimmy was hoping I’d quit because I’d finally made the finals. But I’ll keep showing in cow horse as long as I don’t embarrass Jimmy and my horse.

From a physical standpoint, I’ll need a fifth surgery someday (I had a fourth last March): My damaged femoral artery still isn’t pumping at full capacity. As for after effects, I don’t ride colts or young horses any more. And, I went from 14 customer horses to just five, due to the accident. I don’t blame the customers. When you put a horse in training, you want it to be trained. And I couldn’t train for a while.

But my wreck had a huge silver lining. I learned how many people truly care about me. I’ve lost my husband and a brother, and only have one brother left. I used to catch myself thinking, “I’m all alone.” But after the accident, I got two huge grocery sacks full of cards. Some said, “I’ve never met you personally, but I feel as though I know you from watching you all these years at shows….” People I hadn’t talked to in 30 years called.

Jimmy, Kim, and my customers (even those who left) make sure I’m taken care of. I know now that I’m not alone in this world. I feel very loved. And I don’t sweat the small stuff anymore. The accident gave me a new perspective on life. I shouldn’t even be here. So I’m darn sure going to make every day that I am count.