Editor’s Note: Read part one, The Slaughter Debate: A Two-Sided Issue.

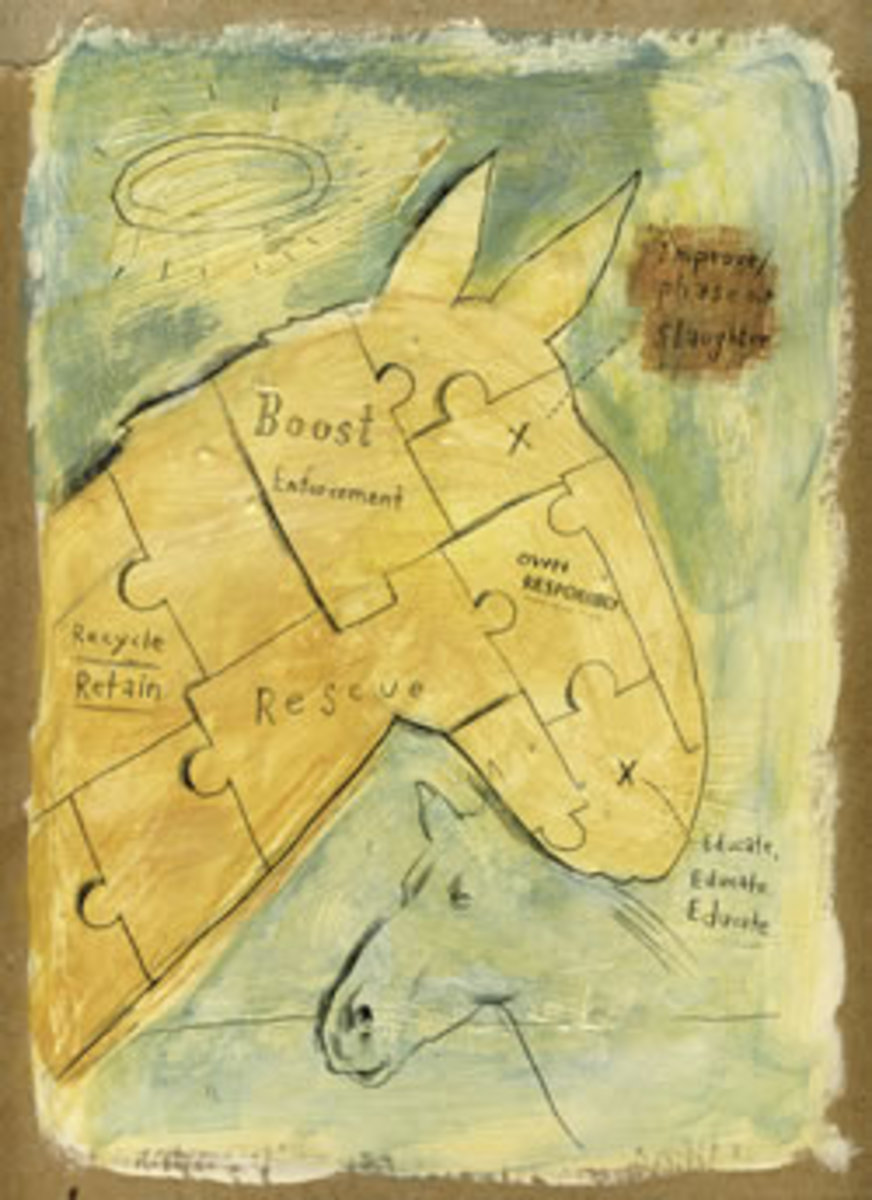

What’s the answer to the question of unwanted horses? The scope of the effort behind current and proposed anti-slaughter statutes shows that slaughter is becoming increasingly controversial. Yet alternative solutions for horses currently being sent there are neither straightforward nor easy.

“There’ll always be animals that aren’t wanted because they’re dangerous, or have a medical problem that makes them unusable or financially unfeasible, or belong to owners whose economic outlook has changed,” says Bonnie Beaver, DVM, MS, Diplomate, ACVB, of Texas A&M University and former president of the American Veterinary Medical Association. The dilemma arises, she adds, when no one else can or will take on the responsibility for such horses.

In 2006, approximately 100,000 horses were slaughtered in U.S. plants. Finding other alternatives for that many animals will be a challenge. In part two of our special report, we explore a wide range of possible solutions, weighing the pros and cons as represented by those on both sides of the slaughter debate.

Yes, the scope of the problem is huge, and the areas of disagreement are many. Ultimately, solving the unwanted-horse puzzle will require action, commitment, and funding–and not just rhetoric. In the interest of promoting that action, we present this overview of solutions.

Own Responsibly

Everyone agrees that responsible horse ownership is key to solving the unwanted-horse problem. But opinions differ drastically on what “responsible ownership” means. According to the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), it means lifetime ownership.

In other words, no one should purchase a horse unless they’re able and willing to care for it over its entire lifetime–which can last 25 years or more.

“Horses are sensitive animals and, just as we wouldn’t purchase a dog, then realize we can’t care for it and send it to a butcher, we shouldn’t do that to horses, either,” contends Matt Prescott, manager of vegan campaigns for the Norfolk, Virginia-=based PETA.

Bruce Friedrich, head of PETA’s campaign department, also draws parallels to the ownership of companion animals. “Horses should be treated as members of the family. They’re not like cars or other inanimate objects that one simply replaces based on age or for other trivial reasons. If you can’t afford to care for your animal, you shouldn’t have an animal, and you certainly shouldn’t get another one.”

In fact, horses are legally classified as livestock, not companion animals like dogs and cats. So, while horses can and do become members of the family, says Tom Persechino, senior director of marketing services for the American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA), they are different from companion animals. And changing their legal status, he believes, would result in the loss of much that’s beneficial.

“That would include emergency disaster relief for horses, tax advantages for horse owners, equine limited-liability laws, and tracking and containment of equine diseases,” he says.

Even if horses’ classification were changed to that of companion animal, it might still be difficult to deal with them as such. Currently, unwanted cats or dogs are euthanized by the owner’s veterinarian, turned loose to fend for themselves, or surrendered to shelters (where millions are euthanized annually).

By contrast, the at-home euthanasia of a horse is more expensive and involves the cost and challenge of carcass disposal. Obviously, turning a horse loose is not an acceptable alternative. And there’s nothing the equivalent of an animal shelter for unwanted horses, where they’d be euthanized (and the carcasses disposed of) at public expense.

Even if such shelters were available, expecting most owners to keep a horse throughout its lifetime is probably unrealistic. Horses are typically acquired not just for companionship, but also for riding or other endeavors. When a horse’s suitability as a working or recreational partner changes (or when his owner’s needs change), he may be sold to someone for whom he’s more appropriate.

AQHA, the world’s largest breed association, processes roughly 200,000 transfers of ownership each year worldwide, confirming what history shows us: Owners who keep a horse for life are few.

Still, the notion of lifetime ownership is consistent with the overall philosophy of PETA and similar organizations. PETA also opposes horse racing, rodeos and other equestrian venues, as well as some aspects of horse showing. PETA’s Friedrich specifically pinpoints as unacceptable “the sales of horses at auction because their usefulness is at an end or they aren’t successful, and the breeding of horses when so many end up sold by the pound at auction.”

The 8,000-member Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA), based in Colorado Springs, Colo., takes a different view on owners’ rights. A member of the Unwanted Horse Coalition, PRCA runs a column on animal welfare in its Pro Rodeo Sports News magazine, as well as a monthly e-newsletter on the same topic.

“Groups like PETA believe in animal rights, meaning we don’t have the right to use animals,” observes Cindy Schonholtz, PRCA animal welfare coordinator and author of the columns. “PRCA believes in animal welfare–that we do have the right to use animals in industry, sport and recreation, but that along with that right comes the responsibility to provide proper care and handling. We’re working with the industry to help educate horse owners, especially new horse owners, on the responsibility they’re taking on when they purchase a horse.”

Other current education efforts in the industry include a handbook being published by the American Paint Horse Association (APHA) explaining the tax write-off opportunities of donating horses to nonprofits.

“We want to eliminate unwanted horses through education, not legislation,” says Jerry Circelli, director of APHA public relations/marketing and research committee chair for the Unwanted Horse Coalition formed in 2005 (and now part of the American Horse Council).

The Washington, D.C.-based Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) is producing The HSUS Complete Guide to Equine Care on the cost and responsibility of ownership. “It’ll help new owners understand what to do from the day they get a horse to the end of its life,” says the HSUS’s Stacy Segal. “We’re also trying to communicate that there are many ways to enjoy without owning–you can lease, volunteer, provide foster care for rescued horses, attend shows, or volunteer with the Pony Club or 4-H.”

Breed Selectively

Historically, a key role of breed associations has been to promote the production of more members of the breed, and indeed registration fees provide a key source of income for such groups. But as awareness of equine “overpopulation” and its attendant ills grows, associations are feeling pressure to change their approach to this area of the horse business.

“AQHA never said more horses are better–we say better horses are better,” says the association’s Persechino. “If we registered fewer horses each year, knowing no horse would become unwanted, we’d be happy with that.”

In fact, breed associations are limited in what they can do legally to discourage breeding. AQHA learned that lesson in 2002, when a Texas district court ruled that the association had to allow the registration of more than one foal per year from one mare. (With embryo transfer, one mare can produce multiple foals with the help of surrogate broodmares.) Last year, AQHA registered 3,626 foals produced by embryo transfer.

Dan Fick, executive vice president director of The Jockey Club, agrees that associations are somewhat limited in the area of controlling breeding. “Unless it’s legislated as it is in foreign countries, you can’t tell somebody what to do with his horses,” he observes.

What associations can and increasingly are doing, however, is promote responsibility in breeding. “Everybody loves their horse, but not every horse will have marketable foals, and not every horse should be bred,” says Persechino, adding that the AQHA is striving to get that point across to its members through articles in its Quarter Horse Journal and other media.

Fick agrees. “Professionals carefully study pedigrees for crosses, but the person who buys a mare and decides to breed to a local stallion down the road shows little concern for conformation or how difficult it is to raise a foal to a riding horse.”

Besides, he adds, breeding your own isn’t even necessary. “There are plenty of horses out there to buy.”

Tom Lenz, DVM, is former president of the American Association of Equine Practitioners and chair of the Unwanted Horse Coalition. He’s cautiously optimistic but believes reaching would-be breeders that aren’t part of any association is a big challenge.

“Change is starting to happen in this industry–I’ve seen it over the last year,” he says. “But one of the biggest problems is people who breed horses and are not part of a breed or sport organization. They don’t receive industry publications, or they can’t be reached by a vet. I have neighbors with grade horses and a stallion. They breed poor quality–the tough part is getting the word to people like them.”

Rescue/Rehabilitate/Recycle

If we, as owners, can be educated and persuaded to own and breed our horses more responsibly, the number of unwanted or “surplus” horses will drop. But, as Dr. Beaver points out, there still will be a percentage that winds up without someone willing to pay for their care.

For these horses, a rescue program or retirement home may be an option, and in fact is often touted by anti-slaughter advocates as the answer.

The challenge is that existing facilities have an estimated capacity for only about 6,000 horses–not nearly enough to absorb the 90,000 to 100,000 or so animals that have typically been going to slaughter each year. But there’s another way to think of these numbers.

“It doesn’t mean only 6,000 horses can be handled in a year,” points out HSUS’s Segal. “The point of a horse rescue is to take the animal in, give it help, then place it in another home. So the number of spaces constantly changes and the number of horses that can be dealt with is far greater on an ongoing basis.”

Currently there’s no centralized trade organization to count or coordinate horse rescue operations, which are often small, informal outfits that can become financially and physically overwhelmed.

Recognizing this, in July of this year the HSUS and the Animal Welfare Institute (also based in Washington, D.C.) co-hosted “Homes for Horses,” a free conference attended by 22 rescue organizations, with the goal of training them to be more effective and self-supporting.

“Our best role is to strengthen these groups to become self-sufficient,” says Keith Dane of HSUS. “Our own members don’t pay dues, so we can’t support other non-profits on an ongoing basis. But we can give them the tools–a national rescued-horses database, our promotion of adoption as primary, and improved fundraising techniques–to do a better job.”

Toward that end, HSUS is currently compiling a database of horse rescue, sanctuary and retirement groups, plus conducting a survey of the more than 400 known existing rescue facilities. In August 2007, HSUS partnered with the “Pets911” Pet Adoption Network to add adoptable rescued horses to the Pets911 website; currently more than 100 rescued horses are now listed there, in addition to cats and dogs.

Additionally, the HSUS Animal Care Expo in spring of ’08 will offer equine courses geared at law enforcement and rescue organizations.

Other organizations that are taking a lead in rescue and rehabilitation include those involved with the racing industry.

Improve (Phase Out?) Slaughter

It may be that with a concerted effort and adequate funding, the slaughter option could eventually be phased out. Or, as in the United Kingdom (see “How the Brits Do It” on page 44 of Horse & Rider, November ’07), it may remain in a highly regulated form to serve a small fraction of the homeless horse population.

Either way, there’s much that could be done now to make existing slaughterhouses a better option, as in the British system: more and better oversight, plus the requirement that those whose job is euthanizing horses at the plants have extensive horse-handling experience and the disposition/willingness to “go the extra mile” to ensure a peaceful end for each horse. The U.S.’s two largest veterinary associations–the American Association of Equine Practitioners and the American Veterinary Medical Association–both

oppose a slaughter ban for fear it would result in less humane slaughter abroad (especially in Mexico, where more American horses are now being sent), longer shipping distances, and more neglected and abused horses overall.

Chris Heyde, deputy legislative director of the Washington, D.C.-based Animal Welfare Institute (AWI), sees it differently. In 2002, Heyde co-wrote H.R. 503, the slaughter ban legislation, with Liz Ross of AWI and Congresswoman Connie Morella (R-Maryland).

“Our goal is a federal ban–when it passes, we can control transport,” asserts Heyde. “We don’t want horses going to slaughter in Mexico, either. If horses are going to Mexico for breeding or sale, they’ll have to have vaccination records, be put in quarantine, and have brokers to get the horses out of quarantine. If you’re a killer buyer looking at only a $50 profit per horse to begin with, you’ll lose money.”

Heyde adds that donors who fund AWI efforts to curtail horse slaughter will also support efforts to strengthen state animal abuse laws (in many states, animal abuse is still a misdemeanor) and fund additional humane investigative police officers.

More funding would also be needed for local governments that oversee animal welfare issues.

“Currently when a horse is seized for humane reasons, payment for its upkeep is on the back of the county,” points out Ginny Grulke, executive director of the Kentucky Horse Council. “That provides a disincentive for the county to process humane cases, because they don’t have the funds. We need to help law enforcement authorities, sheriffs, animal shelters and police be able to confiscate a horse and have funding to keep it, and also possibly charge the owner for the upkeep until the owner goes to trial. That way, cases can be tried, and courts and counties won’t be financially discouraged to follow through.”

Temple Grandin, PhD, University of Colorado animal scientist and humane slaughter facility specialist, believes much can be done to reduce the need for slaughter, but that the option will still be needed for a small percentage of horses.

“With better education of novice buyers, education of owners on overbreeding, funding of sanctuaries and recycling of horses to other careers, maybe we can get down to needing only one slaughterhouse in this country,” she postulates.

The AQHA’s Persechino also believes the slaughter option should remain, “but in a more enforced and supervised way, just as transportation to slaughter should be improved. In addition, auction houses and sale companies could be more responsible in letting sellers know that their horse could go to slaughter.”

Ideally, he adds, “we’d also invest in properly funded euthanasia stations. “This last is an idea others have tossed around, as well, as a way to provide horse owners with subsidized euthanasia and carcass disposal.” But, again, funding is the sticking point. The AWI’s Heyde would like to see industry and breed organizations collaborate with humane groups to create such nationwide low-cost, pro bono euthanasia programs.

Working Together… Or Else

Clearly, opinions differ widely on many aspects of dealing with the problem of homeless or unwanted horses. But on some aspects, all who care about horses can agree. Perhaps the most important area of consensus is expressed by the Kentucky Horse Council’s Grulke.

“Every sector of the equine industry must join together to address this problem in the interest of the welfare of the horses,” she asserts. “If we don’t, forces may come from the outside and impose rules, and it may not be the answers we want–such as legislating how you can breed. We need to be responsible.

“It’s just as with any industry,” she adds. “If we have a problem, we should work together to solve it. It’s time.”

This article originally appeared in the November 2007 issue of Horse & Rider magazine. Pick up a copy of the issue to find how the United Kingdom limits its need for slaughter, suggestions for what you as a horse owner can do to help, and a list of innovative solutions to the problem of unwanted horses.